Bartleby's Daughters

Girls, retreating to the moon

I want to walk in the snow / and not leave a footprint.

I want to walk in the snow / and not soil its purity.

‘4st 7lb’, The Manic Street Preachers

Female choice is the greatest force in nature. It can make or destroy species - and civilisations.

We live in a period in which the consequences of female choice-making are more significant than they have ever been. This is because it has now become possible for women to choose, to a greater extent than ever before conceivable, whether to have children at all, how many, and with whom - from a potentially almost limitless array of potential partners. Nobody should (I hope it goes without saying) advocate for a moment returning to a time when they were not so free to choose. But we have not yet even begun to reckon with the consequences of this - in historical terms - extraordinary development.

This was brought home to me while reading three discomforting newspaper articles over the past few months. The first, an op-ed in The Telegraph, has a headline that tells you everything you need to know about the article itself: ‘Population decline will destroy the West as we know it’. Our populations are declining; birth rates are jumping off cliffs like lemmings; the result will be deteriorating living standards and the deathly struldbrugism that will flow from political power accumulating in the voting block of the old. The second article, in The Daily Mail, offers us an insight into the ‘disturbing world of femcels’, an online subculture of women who have given up on romance, dating, marriage, childbirth, and so on, either because they consider themselves too unattractive or because they have been totally put off by porn or bad experiences with the disgusting and violent/sexually aggressive behaviour of some man or men. And the third article, in The Guardian, features Daniel Kebede, General Seretary of the National Education Union, describing how the widespread availability of ‘aggressive hardcore pornography’ is fuelling a ‘culture of misogyny and sexism’ among boys, and seriously disrupting teaching in schools as a result.

Any fool can see that the three problems are linked. To a certain extent it seems obvious that something about the material or socio-economic conditions of late modernity tends to result in fewer children being born - that trend is evident everywhere. It is probably also true that there is some effect on the birthrate, at the margins, of ‘climate anxiety’ and environmentalist-driven anti-natalism. But it is even more obvious that the conditions in which many people now live are, not to put too fine a point on it, in psychic terms a bit crap. The many problems associated with smartphones are becoming so obvious that they cannot be denied, but the issue is I think deeper and broader than that - young people now often grow up in a cold, unforgiving environment that can only be described as dehumanising in the sense that it is devoid of genuine human connection.

Never mind the apocalyptic effect of the tsunami of extreme pornography which has been unleashed on society since the widespread adoption of the internet - a vast and unspeakable calamity. Never mind the tinderisation of dating, which has concentrated sexual capital in such a tiny sliver of the population. And never mind the fact that young people nowadays grow up in an atmosphere of mutual recrimination and distrust between the sexes stemming from the pervasive atmosphere of political polarisation, cancellation, cyberflashing, upskirting, and so on and so forth.

Those are really just facets of a more fundamental feature of digital modernity: the reduction of the ‘other’ to a mere avatar or sprite, relevant not because they are a person in their own right, but rather in their constituting a transitory aspect of one’s digital or physical environment. This mode of interaction is fostered by the capacity of the internet to abstract the individual from context - from past or future, from feelings and background - and display him or her as a simple fleeting artefact of the present, soon to disappear into the ether to be replaced by some other avatar.

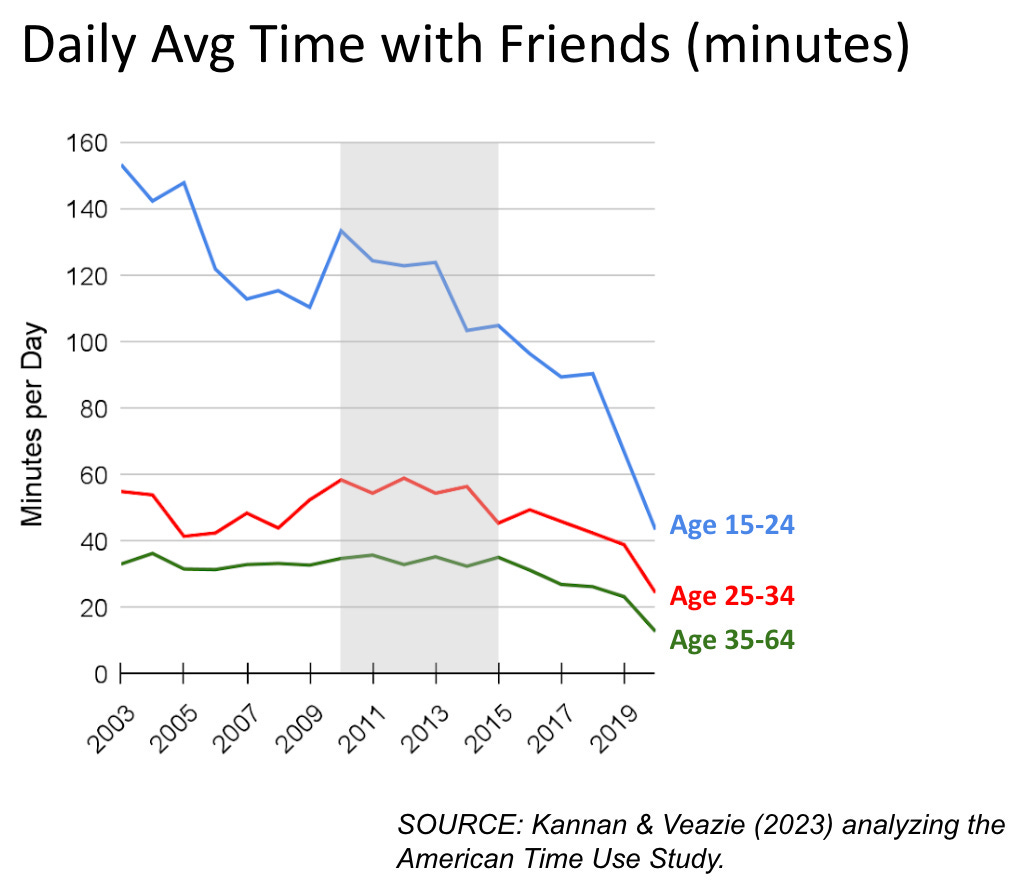

This has two consequences. The first one is a sense of sheer achedia with respect to human relationships in the round - a feeling that human interactions are cheap, superficial, and largely as a result superfluous. Why spend the time getting to know somebody now when there are a billion other people one could briefly interact with online instead? Why listen to anybody in particular when there is so much to hear through one’s ear buds? Why understand anybody’s point of view when they only appear in your awareness as a tweet, blog post or meme before disappearing into the online ether? And, it follows, why go to the trouble of meeting somebody, getting to know them, and falling in love? Why even make friends? From the article linked to above:

The second consequence is a lack of healthy self-esteem. How must it feel to grow up in a world in which literally everybody you meet - your friends, people in the street, even your parents - are more interested in what is going on in their phone, or on their laptop or tablet, than in listening to what you have to say? How must it feel to have most of one’s interactions with others mediated through a technological interface which is tailor-made to distract any potential interlocutor? This can be nothing other than mildly but relentlessly undermining of self-worth, leaving aside the sense of inadequacy that is bred by the competitiveness of social media in the developing mind.

The result of all of this - not for everyone, by any means, but a significant enough chunk of the population to be itself very significant - is a deep malaise, characterised not so much by hatred of humanity but by a vague lack of interest in other human beings as such, and an inchoate sense of disappointment in what life has to offer. Who, enmeshed in that dispiriting web, would want to bring children into the world?

You are likely familiar with the film Seven. In one scene, the Gwyneth Paltrow character, Tracy Mills, confides to William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) that, although she is pregnant, she is considering an abortion on the grounds that the city in which she lives is an unfit environment in which to raise a child. What we are I think witnessing is a much less dramatic but more pervasive playing out of that logic; a feeling amongst many young people that, since life in the digital age is, to use what seems to be the appropriate term, a bit ‘meh’, then having a baby is likely to be a bit ‘meh’ for parent and child alike. Why afflict that sensation on either party by going through the rigmarole in the first place?

The Japanese fairy tale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (often referred to in English as The Tale of the Princess Kaguya) sheds a great deal of light on this. (If you have not yet had the opportunity to see it, I strongly recommend Takahata Isao’s wonderful animated version, available on Netflix. Make sure you watch the subtitled, not the dubbed, edition.)

The story is one of the great contributions of Japanese civilisation to world folklore. In it, an elderly childless couple discover a tiny baby girl (Kaguya) hidden inside a bamboo shoot. They decide to raise her as their own, and she quickly grows into a beautiful woman; they also find in the bamboo forest gold and rich gowns with which to give her a life of luxury. She attracts many suitors, to whom she sets impossible tasks in order that they might try (and fail) to win her hand in marriage, and eventually even the Emperor of Japan tries to make her his own. But ultimately she rejects even him, and is in the end spirited away to the moon, which, it is revealed, is her true homeland, from which she was exiled for some unknown crime. Her parents are stricken with grief at her disappearance and, it is implied, then sicken and die.

As is so often the case with these stories, the tale asks us to hold in our minds two competing dispositions - in this case, to the task of giving birth and raising a child. On the one hand, to have a baby is wonderful: it produces something beautiful and vastly enriching. But on the other, to do so is to invite into your life great tragedy; the person that you love more than anything else will by necessity leave you, both in the sense of outgrowing you and in the sense of physically going out into the world. He or she will also, undoubtedly, in turn also suffer. And sooner or later you will grow old and die and your connection to that person will in any case be forever severed.

Having children is, therefore, neither wonderful nor tragic - it is both at once. And one cannot, indeed, have the wonder without the tragedy. Every parent must reconcile him- or herself to heartache; the only real question is just how much heartache there will in the end be.

This makes having babies a leap of faith. It will make you happy, but also make you sad (and, of course, for most of human history it could also quite easily literally kill the mother - making the leap of faith a visceral one indeed). It is hardly surprising, then, that many modern young people, for whom life, as we have seen, is already often rather insipid and pointless, should not want to embrace parenthood, and should indeed view it with trepidation as involving too much potential pain and suffering to be worth doing. Wonder and tragedy do not appeal, because life is not known by these people to contain such things; they are used to inhabiting an altogether more staid, arch and banalified reality, and view anything that intrudes upon it with trepidation and hostility.

As a father of daughters, I am particularly interested in how this all affects girls in particular. The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, for all that the title suggests it is about the father of Kaguya, is very much concerned with matters of the feminine. Even the Emperor of Japan himself is in the end held to be essentially without consequence when set against the interests of Kaguya. The tale positions her at the heart of the matter. And, in particular, it seems to position her choice-making as the crux of everything. She will choose who to marry - or not. Her suitors are desperate to win her hand. Even the Emperor wants her. But she will not be moved. Her decision is her own.

In one respect, this speaks to an ancient truth that any straight man reading this will appreciate: the deep and inscrutable mystery that is female decision-making in matters of the heart. Men, when it comes to sex, are simple creatures - we are, rather famously, not particularly discerning. Women are different. This means that, by and large, the choice-maker in such matters is the woman. The result is that young men spend inordinate amounts of time trying to figure out what it is that will make the target(s) of their affection find them appealing. We have a vague idea that it isn’t merely looks. So what is it? Is it fashion sense? Is it success, money, a good sense of humour, creativity, being sensitive, being a bad boy, being friendly, being aloof? Is it being good at sport, or good at playing guitar? Is it shared interests, or will opposites attract? Should I ‘be myself’ or somebody else? What if I was the Emperor of Japan? Would she like me then?

In this regard, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter has a great deal to say about certain features of male-female relations which seem immutable across space and time. But there is also something deeper going on in the story. Because while Kaguya might be free to choose from her suitors, in the end of course she makes no choice at all. Rather, she - like Bartleby - ‘prefers not to’. Her decision is to make no decision, until ultimately the decision is forced upon her to retreat from the world and into the heavens from whence she came.

It is ambiguous as to whether her reluctance to marry stems from a desire to avoid material attachments (knowing that she must one day return from her exile to Earth) or dissatisfaction with her options. But at root the symbolic message is the same, and seems a kind of foreshadowing or reverse echo of the future we now see quite clearly before us, wherein young women are en masse ‘preferring not to’, and in many cases indeed metaphorically retreating into the night sky, away from the world with all its anxieties, disappointments, and drift. (It is undoubtedly significant that when men retreat from the world they go symbolically or actually downwards, into basements, cellars, caves, chasms, where they become enmeshed in video games, porn, and misogynistic online content. Just as men are from Mars and women from Venus, men it seems are chthonic, while women are celestial.) This could be because of a desire to avoid childbirth and child-rearing entirely, or it could be the result of a lack of acceptable options - or, obviously, both.

Female choice matters, the implication of the tale would seem to be - and in truly civilisational terms. Remember that when Kaguya returns to the moon, her parents are stricken with grief - they will never recover and are in any case too old to have children of their own. It is also interesting in this regard that in some tellings, Kaguya sends the Emperor an elixir of immortality just before she leaves - which he then orders burned, since he does not want to live if he cannot ever see her again. When women as a whole come to ‘prefer not to’, in other words, the results can become cataclysmic. The means by which the civilisation will endure will dissipate in the sense, obviously, that no babies will be born, but it will also suffer a mortal blow in terms of morale: its men will have nothing left to really live for. Even if granted immortality, they will not take it - because why go on if there are no families, no children, no girlfriends, no wives?

I am no reactionary. If anything I lay the blame squarely on men’s shoulders for having so pitifully neglected the raising of good, honest sons who women will find appealing. And I am glad that my own daughters will have choices that would have been entirely unavailable to them if they had been born a hundred or so years ago. I also have no desire to display insensitivity to the many people who would very much like to have children if only they could - or indeed who prefer members of the same sex as partners in life. Nor do I wish to be seen to be implying that childbirth and childrearing are all that women’s lives ought to revolve around.

But, all the same, I look to the future that stretches ahead of us with a sense of foreboding. We have, inadvertently, created the conditions in which love, commitment, and family have either lost their appeal, or are slipping out of reach. The result is that many young women, Kaguya-like, increasingly if unconsciously come to see their life in the world as a mere transition or phase that will leave no trace behind it when it ends - a kind of exile before their eventual return, into themselves and from thence to the moon. They are exercising their choice, and they are choosing not to.

Given the conditions in which they have been raised, and given what is often on offer in respect of the young men by whom they are often surrounded, I do not really blame them. But it is both a tragedy and an incipient crisis. It is a tragedy because a life without love, without family, is for the vast majority of human beings a sad and humdrum affair. And it is a crisis because it means that in the long-term our civilisation will cease to endure. One of the fundamental features of the human condition is that men and women must collectively come to terms with each other’s existence, and join forces against the world together in raising families. Nobody, I hope it goes without saying, has lived any less of a life if they cannot have children, choose not to do so, never meet anybody they wish to settle down with, or are not attracted to the opposite sex. But nonetheless if by and large men and women in a given society do not form long-lasting, loving, mutually supportive relationships with one another in which to raise kids, then that society will, in the most literal sense, not survive. This then is a matter of the deepest, utmost seriousness - one of the many problems we face that simply cannot be resolved by politics, and which increasingly come to seem intractable if our current arrangements continue as they are.

The acceptance of single parenting as something perfectly normal has alot to do with boys having no decent role models. The loss of industry means men no longer have physical jobs, personal pride in making things, practical knowledge, a sense of purpose and an ability to provide enough to support a family. Working as a Deliveroo driver or Amazon warehouse operative doesn't give men the self confidence working in a steel plant or on an oil rig. The world has become feminised and boys/men are meant to be masculine not feminine. So they end up watching porn, playing computer games involving killing pretend people, not caring and disliking women for apparently usurping their position and not appearing to particularly want them.

Which has the knock-on effect of making girls/women feel they don't need/want men around them. It's a sad, self-fulfilling tragedy which has simply been made horrendously worse by the drowning of the world in technology, the normalisation of pornography, the continuous barrage of anti-men/anti-white/anti-christian propaganda.

Touching, topical, tender.

Tinkling chimes in the memorial corridors

Resonant, reverberating, heralding

Thank you for your thoughtful erudition.