#being kind through a cloud of hatred

A potted history of political compassion, from Robespierre to Lenin to Josselyn Berry

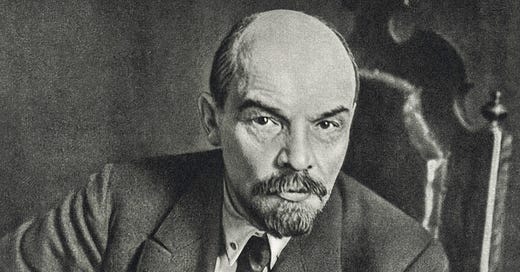

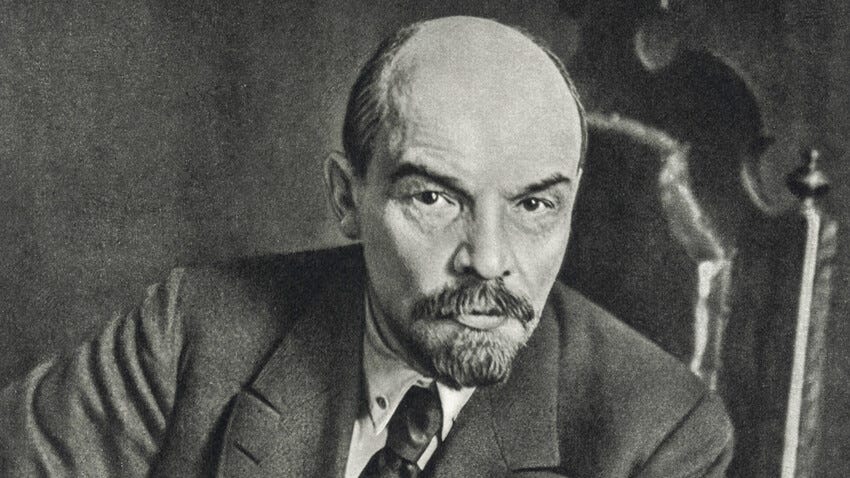

Maxim Gorky once gave a thumbnail sketch of Lenin that bears committing to memory as the description of a commonly encountered archetype. Lenin, Gorky said, loved humanity. But he perceived it through a ‘cloud of hatred’. This odd dichotomy is everywhere amongst political progressives. Imbued with compassion in the abstract, they are capable of immense cruelty in practice. They pity humanity, but at the same time they despise it.

Hannah Arendt provides us with the most useful explanation for this strange phenomenon in her writing on Robespierre (which I wrote about much more extensively here). ‘Compassion,’ she tells us, ‘is the most devastating political emotion.’ To one who has become imbued with the desire to alleviate suffering, every hindrance seems an affront, and every pause a betrayal - because who can be against the alleviation of suffering but an irredeemable fool or monster? The overriding duty of all good people ought to be to cooperate in the cause - and therefore anyone standing in the way can and should be removed, as by a surgeon’s ‘cruel and benevolent knife’ (Arendt’s phrase).

The actions of men like Robespierre (who had over 2,000 Parisians executed over the course of a few months for crimes such as writing, or ‘hoping’ for the wrong things) and Lenin (who thought nothing of starving millions of his countrymen in the name of the revolution), do not, in other words, gainsay or count in contradistinction to their strong sense of compassion. The truth is quite the opposite: compassion and cruelty fit one another hand in glove when the former is transposed from the realm of interpersonal relations, where it belongs, to the realm of politics, where it does not.

Anyone seeking to understand internet mobbing and cancel culture - in which hordes of Twitter uses with #bekind in their profiles drive perceived enemies to financial ruin or even suicide and bray with delight about it afterwards - must understand this crucial feature of the modern psyche. Likewise, it readily explains the bizarre spectacle of the press secretary for a Democrat governor of Arizona celebrating the deaths of children from a community which took the ‘wrong’ stance on trans rights. The people who participate in these kinds of actions do not lack compassion - far from it. If anything they have a surplus of it. But that is entirely compatible with the malice of their actions. They wish to alleviate what they perceive to be suffering. And they are wielding the ‘cruel and benevolent knife’ accordingly against anyone who stands in their way.

We stand at an inflection point, at which we see political violence against those with the ‘wrong views’ (of whatever stripe) teetering on the brink of becoming normalised. At such a time, it bears remembering we have been here before, on many occasions. This may not help us prevent it. But by remaining attuned to what motivates those who engage in it, and reflecting on how politicised compassion can blind people to the consequences of cruelty, we can at least avoid falling down that same precipice ourselves.

Very well written it reminds me of the C.S. Lewis quote

Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron's cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

The twenty first century risks being remembered as the time that kindness was weaponised.