Lawyers are the first refuge of the incompetent.

-Aaron Allston

It is not, I suppose, so strange to encounter a middle-aged man complaining that people are getting stupider. But I am going to go out on a limb nonetheless: people are getting stupider. And I will go yet further. They are also getting lazier, pettier and sloppier.

A recent vignette from the High Court of England & Wales is highly apt in this regard. Now, a High Court judge telling off a barrister would not normally generate headlines. That has been going on, presumably, since there have been such things as judges and lawyers. But Mr Justice Ritchie’s dressing down of a certain Sarah Forey in his ex tempore judgments in the otherwise bog standard case of R (on the application of Ayinde) v London Borough of Haringey [2025] EWHC 1040 (Admin) have - forgive me - ‘sent shockwaves’ through the legal profession in England & Wales.

Much of the fuss has centred around the fact that Ms Forey is (probably) the first barrister to have been publicly caught out using AI to do her legal research. As anybody with any sense who is involved in legal education knows, since AI is not actually meaningfully ‘intelligent’, one can’t rely on anything it comes out with - it produces too much fake information. Ms Forey, not realising this, cited a handful of cases in her statement of facts and grounds in judicial review proceedings that did not exist - they had simply been generated from thin air by whatever AI software she was using (although it is important to make clear that AI use was only strongly suspected, and not proved).

This is appalling, of course. But a lot of the commentary on the subject has focused on the AI issue in isolation. This means that something important is being overlooked: a total hollowing out of our professions that has very deep roots, and of which over-reliance on AI is merely a symptom rather than a cause. I will discuss the AI-related issues in what follows. But I would like to focus on the broader problem of what it seems right to call a general malaise in professional competence.

Ayinde first, then. The facts, as I said, are fairly unremarkable. Mr Ayinde was a homeless man who applied for social housing from the local council in the summer of 2023, providing medical evidence that he ought to be a priority case due to having a chronic kidney disease and being at risk of heart attack. The council, Haringey, decided that he was not a priority case, and he then sofa-surfed or slept on park benches for a year until he, lo and behold, had a heart attack. He was eventually granted an interim accommodation order by a Deputy High Court Judge in October 2024 pending a judicial review hearing for 3rd April 2025, intended to establish to what extent Haringey Council’s decision not to grant him accommodation had been procedurally improper, had failed to take into account relevant medical evidence, and had been irrational. That hearing, on 3rd April, was the occasion for Ritchie J’s judgments.

The main issue of interest, as I have said, was the fact that the Claimant’s barrister, Sarah Forey, cited five authorities in support of her client’s position - R (El Gendi v Camden [2020] EWHC 2435 (Admin); R (Ibrahim) v Waltham Forest [2019] EWHC 1873; R (KN) v The London Borough of Lambeth on the application of Balogun [2020] EWCA Civ 1442; R (on the application of H) v Ealing London Borough Council [2021] EWHC 939 (Admin); and R (on the application of KN) v Barnet LBC [2020] EWHC 1066 (Admin) - which simply did not exist. They were fake cases. It looks vaguely plausible that they might be real cases. But they’re not. They don’t exist in any law report and cannot be found on any database or in any court records. They can be presumed to have been AI ‘hallucinations’ that were not properly vetted.

I suppose it is obvious why this is bad - firstly, because it misleads the Court, and secondly, because it does not give the Defendant a proper opportunity to defend itself (it being impossible to respond to arguments based on made-up authorities). And on these grounds alone Ritchie J was prepared to conclude that Ms Forey’s behaviour ‘qualifies quite clearly as professional misconduct’ which she ought to have reported to the Bar Council (the regulatory body in charge of barristers).

What was worse, though, was that Ms Forey sought to downplay the significance of the matter by insisting that these fakes were ‘minor citation errors’ and coming up with a confected and utterly implausible explanation - namely that she had accidentally ‘dragged and dropped’ the main fake case mentioned (the purported ‘El Gendi’) and its legal principle, from a digital list of cases she kept, into her statement of facts and grounds. Ritchie J’s comments on this, while I am sure they were delivered with a straight face, cannot help but raise a smile and are worth reprinting in their entirety:

What I was told from the Bar today by Ms Forey is that she kept a box of copies of cases and she kept a paper and digital list of cases with their ratios [i.e., their precedents] in it. She dragged and dropped the case of El Gendi from that list into this document. I do not understand that explanation or how it hangs together. If she herself had put together, through research, a list of cases and they were photocopied in a box, this case could not have been one of them because it does not exist. Secondly, if she had written a table of cases and the ratio of each case, this could not have been in that table because it does not exist. Thirdly, if she had dropped it into an important court pleading, for which she bears professional responsibility because she puts her name on it, she should not have been making the submission to a High Court Judge that this case actually ever existed, because it does not exist. I find as a fact that the case did not exist. I reject Miss Forey’s [sic] explanation.

And what was even worse was that, when the Defendant, Haringey Council, made a submission for a wasted costs order to the Court (seeking compensation for the cost of their time spent having to deal with fake cases), Ms Forey made a further submission containing more suspicious-looking case names and without giving the judge or Defendant copies. Ritchie J again:

So, for instance, in relation to El Gendi, Ms Forey referred to R (Kelly & Ors) v Birmingham [2009] EWHC 3240 (Admin). Quite apart from never having provided that authority to the Defendant, and never putting in any written response to the Defendant’s wasted costs application, Ms Forey did not provide a copy to me, so I have no way of knowing whether that case exists or, if it does exist, whether it supports the proposition of law which she put into her statement of facts and grounds. This is not the right way of going about defending a wasted costs order or citing authority.

This is all terrible, of course, for Sarah Forey, whose career, it seems safe to say, is now in tatters. But it is important to emphasise that, as bad as her conduct was, it must really be understood as simply the cherry on the cake of an absolute litany of incompetence, responsibility-shirking, and corner-cutting on the part of almost everybody involved in the litigation at every level.

The first thing to observe in this regard is that the Defendant, Haringey Council, was debarred by the judge from even defending itself in the hearing, because, in essence, it had almost completely failed to comply with various court orders requiring it to file necessary documents in advance. And it was able to offer no sensible reason for this failure. To quote Ritchie J again, ‘The witness statement explaining why says little more than: “We didn’t. It was my predecessor’s fault.”’ The whole thing - with tens of thousands of pounds of taxpayers’ money at stake - was dealt with by the Defendants along the principle of ‘The dog ate my homework’.

And the second thing to observe is that the Council’s conduct in respect of the Claimant was simply dreadful throughout. Having been sent an initial homelessness application by Mr Ayinde in June 2023, with evidence of his chronic kidney disease and hypertension, the Council had inexplicably decided he was not a priority case, which was bad enough. But it also ignored a letter, sent a month later, from a doctor at the Royal Free Hospital expressing extreme concern about the Claimant’s prospects for survival if he remained homeless, and another letter from his GP observing that if he remained homeless he would be at ten times the risk of heart attack or stroke than he would otherwise be. In October 2023, the Council ignored a further letter from a doctor insisting on the urgency of Mr Ayinde’s case and that he was awaiting ‘life-saving treatment’.

All that happened in response to any of this was a medical report given by the Council’s medical advisor to the effect that ‘There is nothing serious to suggest [Mr Ayinde] requires urgent or operative intervention or that his kidney disease adversely affects him day to day.’ This, as Ritchie J put it, is ‘remarkable and surprising’ given the evidence that had been adduced, and can surely only be attributed to a basic failure to bother properly investigating - with, let us be clear, somebody’s life at stake, never mind money.

But that is just the Defendant, Haringey Council’s, conduct. We have already been through the ‘fake case’ aspect of this, but this was hardly the end of the errors and sloppiness on display. Foremost among these was a patent misstatement of the applicable law. Although in the end it was immaterial to the outcome, Ms Forey had made the case that the Council had a duty to provide Mr Ayinde with accommodation, since he had asked for a review of the decision not to identify him as a ‘priority need’. Ms Forey asserted that s. 188 (3) of the Housing Act 1996, the relevant statute, provides that a local authority must provide interim accommodation pending the decision in such a review. But the statute does not say this. Rather, s. 188 (3) reads:

[T]he authority may secure that accommodation is available for the applicant's occupation pending a decision on review

‘May’ is not ‘must’. Anybody reading the statute properly would have identified this - let alone a barrister purportedly expert in housing law. But Ms Forey’s grounds simply stated its contents incorrectly.

And then we come to the Claimant’s solicitors (Haringey Law Centre) - where the right question to ask might be, ‘Where does one start?’ How about with the fact that on the 16th of August 2024, they wrote to the Defendant requesting to provide accommodation for their client by the 14th of August (a letter which, incidentally, the Defendant completely ignored)? Or the fact that at that time they, for reasons known only to them, did not make an application for urgent or interm relief for their client, which may have resulted in emergency accommodation being provided and his health problems being forestalled?

But perhaps it is best for current purposes just to direct your attention to the bizarre letter that was written by a certain Sunnelah Hussain, of Haringey Law Centre, to the Defendant Council on 3rd March 2025, after the ‘fake case’ issue had been exposed and put to her firm and to Ms Forey. Here are the opening sentences in it:

Thank you for your email. We write in respect of your letter dated 13 February 2025 on the matter at subject is referred. [sic]

Becoming only marginally more coherent, it disputed the importance of the fake cases:

We regret to say that we still do not see the point you are making by correlating any errors in citations to the issues addressed in the request for judicial review in this matter. Admittedly, there could be some concessions from our side in relation to any erroneous citation in the grounds, which are easily explained and can be corrected on the record if it were immediately necessary to do so… So let us agree that the citation errors can be corrected on the record ahead of our April hearing. Apart from adding our deepest apologies, we do not consider that we are obliged to explain anything further to you directly. You may better serve your organisation by giving attention not to the normative discoveries you have made, but whether you can locate the authorities in support of the points raised, which points you are clearly in agreement with, as demonstrated both by conduct in offering the necessary relief to our client and acting in accordance with the mandate of your client.

And it continued with a further aggressively semi-literate flourish:

We hope that you are not raising these errors as technicalities to avoid undertaking really serious legal research. Treating with citations is a totally separate matter for which we will take full responsibility. It appears to us improper to barter our client’s legal position for cosmetic errors as serious as those can be for us as legal practitioners.

As Ritchie J pointed out, this was all ‘grossly unprofessional’. Leaving aside the issues with syntax and the basic failure to communicate effectively, the content of the letter is dreadful. It sought to dismiss the fact that fake cases had been cited in the statement of facts and grounds as ‘cosmetic’ or a matter of ‘technicalities’. It disavowed any requirement to explain or justify the use of false authorities (‘We do not consider that we are obliged to explain anything further to you directly’; the errors are ‘easily explained and can be corrected on the record if it were immediately necessary to do so’). It cast aspersions on the Defendant’s own solicitors (‘We hope that you are not raising these errors as technicalities to avoid undertaking really serious legal research’), transparently as a way to deflect attention from Haringey Law Centre’s own shortcomings. As Ritchie J himself put it: ‘[I]s that a professional way forwards for solicitors of the Supreme Court who have produced fake cases, or who have not spotted that counsel has produced fake cases?’

In the end the correct result was achieved in that Mr Ayinde got his interim accommodation and, presumably, ended up being classified as a priority case. But what are we to make of the way the litigation was conducted?

Clearly this is a particularly bad example of modern day professionals conducting themselves in a slovenly way. But it is worth reflecting on the broader trends which it brings to light, and which are in any event I think familiar to anybody who observes their surroundings and the direction in which things are going. Consider:

Almost everybody involved here, it is worth recalling, would have gone through 14 years of schooling and then attended university for three years, and done more legal training after that. But the sum total of all of that accumulated educational experience is a basic inability even to write, or read, properly. Anybody who qualifies as a barrister should be in, let’s say, the top 10-15% in terms of academic ability amongst a given peer group. Yet here we saw exposed a barrister who not only used AI (apparently) to write and do legal research, rather than doing it herself, but who was also seemingly incapable of reading and understanding a statute.

The lack of professional pride on display is astounding. There is nothing particularly wrong with using AI in some contexts, I am sure. I know people who use it for all sorts of purposes, and apparently (according to them) to good effect. But in the same way that a professional would never put his or her name to the work done by somebody else, and certainly without carefully vetting the contents, one should as a matter of pride never pass off as one’s own work material that has been spat out by algorithm. And one should at the least very carefully check, when using an unintelligent tool, as AI is, that it is not making unexpected errors. This is a point that ought to be so obvious as to go without saying, but apparently it is not; to many people, it seems, laziness and corner-cutting trump professional pride.

There is in evidence, in general, an elementary failure to do things properly and carefully. How can it be that a man can submit an application for accommodation to his local council as a priority case and adduce plenty of medical evidence to support that application, and be not just denied but largely ignored? How can it be that letters in his support written by medical specialists were overlooked? How can it be that a local authority facing potentially very expensive litigation failed to submit documents mandated by court order in a timely fashion? How can solicitors fail to check dates on their own letters?

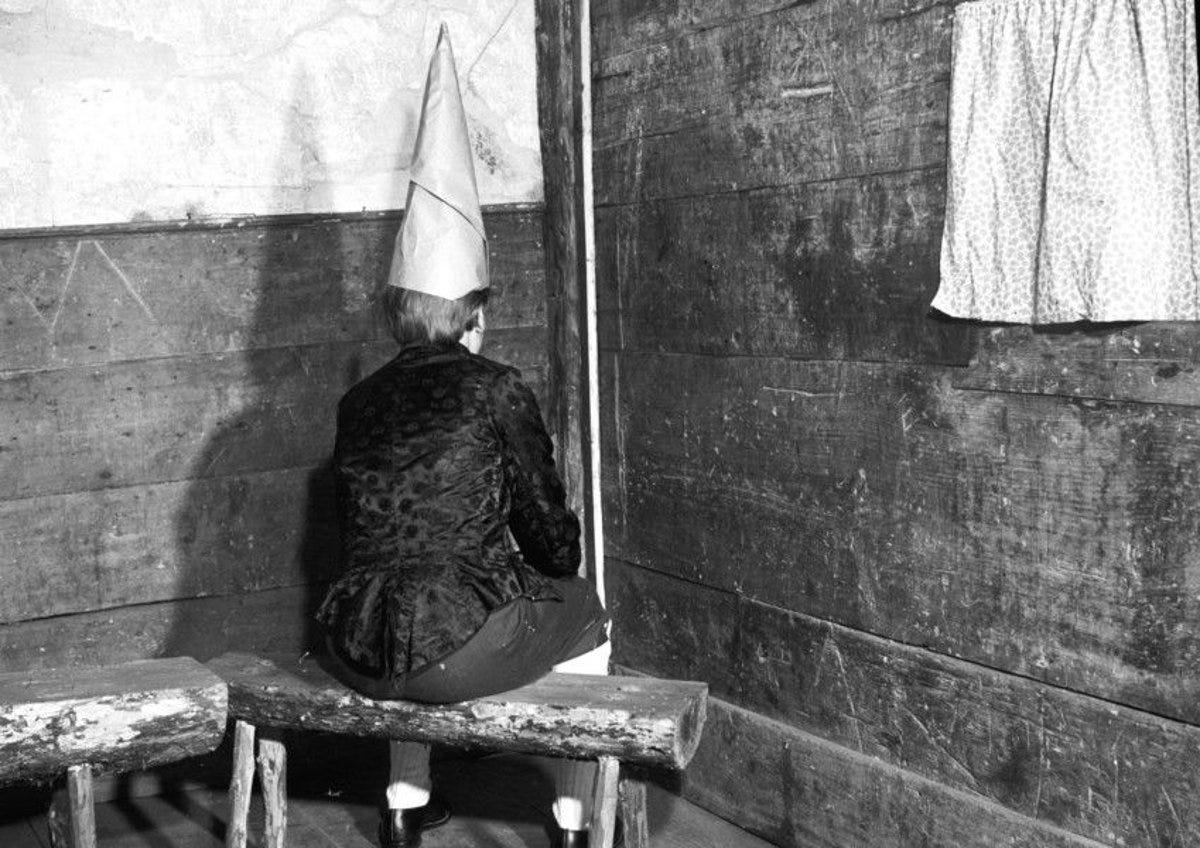

What is perhaps worst of all is a failure to simply own up to mistakes and properly apologise - hinting at a deeper failure to take responsibility for one’s own conduct. Note how blithely the protagonists here (who, to repeat, are all supposedly legal professionals) dismiss their own mistakes, or those of the organisations they represent - whether it is Yisroel Greenberg, representing the Council, who blamed his predecessor for the failure for documents to be filed on time, or Haringey Law Centre, waving away an accusation of having produced fake cases as pertaining to a ‘cosmetic’ matter that was ‘easily explained’, but not worth bothering to explain at the material time. It all comes across as an almost childlike refusal to accept that, as an adult, one has to take responsibility when one has done something wrong - and that one even sometimes has to take responsibility for what one’s organisation has done wrong when not personally at fault.

These trends are everywhere in the present environment. No doubt they have always been present to a certain extent. But I think you will agree with me that they are becoming pervasive. What explains it?

First, no doubt it is partly an effect of technology. In short: it’s the phones, stupid. It is incredible that there is still a social debate going on about the extent to which phones destroy attention spans and the ability to read, since it is so self-evidently the case that they do both of those things. The truth, indeed, is so plain that one has to be wilfully purblind to deny it. A very significant proportion of adults, and a disturbingly large proportion of children, are simply addicted to their phones - although ‘addiction’ is perhaps too weak a term. They cannot go for five minutes without looking at them. Their lives revolve around the technology. And their brains have trained themselves out of the ability to focus or concentrate on anything other than smartphone screens, or else never developed that ability in the first place.

(And that’s leaving to one side the pernicious effects of other modern workplace technology - email being the chief culprit here - which constantly distract attention and cultivate a tendency to perpetually dwell in an inbox rather than develop headspace to complete tasks properly.)

The result of this is that many educated, otherwise intelligent grown-ups can barely read or write at length. They can manage sentences, perhaps paragraphs. But anything beyond that becomes impossible. They zone out. Mature adults are bad enough, of course, but will tend to have the saving grace of having grown up before smartphones were invented, and therefore with some memory of what it is like to have a normal, properly functioning mind. People under the age of 30, though - and I do not blame them for this; it’s society that has let them down rather than the other way around - have no chance. And the result is the type of thing evident in Ayinde: barristers - barristers! - who cannot read statutes, and solicitors who cannot write letters.

Second, though, is the more deep-seated problem, which is what I can only call pervasive half-arsedness. Let’s be clear - it isn’t that the existence of AI is forcing people to rely on it and thereby make mistakes. It is that professional people are frequently relying on AI because they can’t be bothered doing their jobs properly. To repeat my earlier point - I do not wish to deny that AI has its uses. But when one is producing material on which one’s professional reputation will rest, one should really be above using it as a matter of self-respect. Since you will live or die by it, so to speak, your work should be yours.

When I put things this way, though, fellow professionals often look at me askance. And mine increasingly seems to be the minority view. Late last year, I was able to advertise for a funded PhD studentship under my supervision, with very attractive terms and a full-time stipend. I received some excellent responses. But in 75% of applications the research statement clearly, patently, had been written by ChatGPT. And sure enough, when I tested this by asking ChatGPT to write a research statement in response to my advertisement, it produced something exactly like the bland, insipid drivel that these prospective PhD candidates had submitted. We are talking here, let’s be clear, about people with postgraduate qualifications from universities with stellar reputations. Simply unwilling to put the effort in to write a research statement of their own, for what they hope will be their own PhD thesis. This seems emblematic of a deeper malaise - not exactly a desire to avoid hard work (although that is part of it), but a flippancy about its importance.

Third, it is impossible to discuss the topic without addressing the matter of education, and universities in particular. What is going wrong? How can it be that people are completing fourteen years of schooling, three years of undergraduate study, another year or two of training to become a barrister or solicitor, and coming out at the end being incapable of reading or writing properly, and without any sense that tasks have to be done properly?

This is a big topic, and no doubt in part overlaps with the previous two. I am not well-equipped to speak to what is happening in compulsory education, although it cannot be good. But I strongly recommend this post (and the follow-up), written by a professor in the US but speaking for the academic profession I think across the world, to get a flavour of what is happening at university level. As he/she rightly points out, a huge part of the problem is the death of literary culture among the young: the vast majority just don’t read books anymore, because they are on screens - as I observed earlier - all the time. The result is that they simply find it very, very difficult, almost painfully difficult, to parse texts of any complexity.

Universities cannot remedy this because they are not equipped to - they are not schools. And this means that they are having to reorient their activities around having a student body that, more or less, does not read and therefore cannot really ‘study’ in any meaningful sense. Some universities do this better than others (I should say that the university I work for does it rather well), but they are all having to cope with a hitherto unknown situation, in which the most basic skills required for what was until recently understood to be a university education - reading and writing - are not being learned prior to enrolment.

But it is a much wider problem than that; it is not just that university students do not read for the most part. Too many of them also seem somehow disconnected from the experience of living itself - as though the real, physical world around them is a kind of limbo which they are forced to dwell in, in between the times they are able to look at their phones. Studying, reading, cultivating one’s personality, working, preparing for one’s career - these things seem not to matter a great deal. They are out there somewhere, admittedly, but what one holds right now, in one’s hand, flashing lights and unleashing dopamine in one’s brain - that is right here, and that is therefore what demands all attention, focus, and thought. The result is a feeling of detachment from the tasks one knows that one should be doing, and a sense of archness, of remove, of passivity - even enervation.

To repeat: I do not blame students themselves for this attitude - it is the world which they have grown up in. And I do not wish of course to generalise too sweepingly. There are those who passionately care and wish to do well. But the consequences for the professions, which still rely for the most part on a university education, of this hollowing-out of a generation of young people are truly dismal. People are graduating who are ill-equipped to work - not because they lack intelligence or ability, but because they have not spent the necessary number of hours developing the skills they need. And they have not spent the necessary number of hours developing the skills they need because of the effects of the technology in which they are immersed, and because they inhabit a world in which, by and large, fewer and fewer people take pride in their work to begin with.

Putting things that way I suppose makes matters seem rather simple, if bleak. And so, I am sad to say, is forecasting what kind of future is likely to play out, at least until things get so bad that there is a course correction. Competence is on the way out. Things will get worse. This will not happen in a ‘big bang’ moment. Rather, it will unfold gradually but inexorably as the number of competent people in society declines in proportion to the incompetent, and as the expectation of competence declines further yet.

It is important to reconcile oneself to this, and prepare accordingly: the world before 2008 is not coming back. A side-effect of this is that we are likely to see more, many more, instances of cases like Sarah Forey’s, as people come to increasingly rely on AI to pick up the slack and discover that it is half-baked. But the main effect will be that we will also see living conditions further deteriorate as competence declines - and further misguided insistence that technology will be the answer rather than an accelerating factor. This is something to digest and think about very carefully in planning for the future, because it may very well mean growing old in an environment in which living conditions are worsening rather than improving as sloppiness both deepens and spreads. Otherwise, I humbly suggest we all cross our fingers and hope that the point of deterioration at which a course correction becomes inevitable is not as far off as it currently appears.

I believe the key word here is "professional".

Over the years, including before the interwebs and mobile phones, there has been a general de-skilling of the 'professional classes'. Solicitors now use their clerks and conveyancers to do their work (sometimes without adequate supervision). A great deal of teachers' work is now carried out by teaching assistants. Many companies now deal with customer issues through an obligatory help desk - usually staffed by people who have no knowledge of the companies workings, only a stubborn insistence on following a script. You could even make an argument that many MPs rely on their office staff or party instructions too much and don't ascertain the facts properly. One of the consequences of the de-skilling is that bureaucratic rules proliferate to help the minions do the job.

Another consequence is that ordinary people often feel obliged to monitor any professionals they engage very closely, or seek help on user forums rather than tangle with a help desk.

All of which leads me to speculate that we are seeing the slow death of professionalism. We are becoming a 'do it yourself' culture because those we trusted are no longer reliable.

I fear that the professional incompetence you describe is not confined to the Law (where the consequences are mainly monetary).

This reliance on technology reminded me of some seminars I attended a couple of years ago when I did a module on the Law of the Sea at a Russell Group university, as part of a taught Masters. We were about a dozen students, of whom 9 or 10 were Chinese. The Chinese contingent sat masked and silent through every class with their laptops open in front of them. I called them the Great Wall of China. It was quite unnerving because, even in the face of direct questioning by our very engaging and affable lecturer, they would remain mute. (Meaning of course that the other British student and I would say anything at all, even if it was nonsense, to simply not leave him hanging!) When I looked over at what was on the laptop screens of the masked ones, I was astonished to see that the computers were transcribing the spoken word into written word (English), absolutely perfectly, whilst the human bricks in the Wall were playing computer games on a split screen!

I always wondered afterwards, how their essays turned out.