Slowly but surely, marriage and family life (and the birth rate) are becoming salient political issues, at least among conservatives. It is instructive therefore to consider marriage in light of the recent discussion concerning different approaches to ‘the moral life’. This is because the decay in marriage, and the various crises to which it has given rise, indicate the extent to which we have become beholden to a highly detrimental type of moral thinking, and shows us the damage that this is wreaking on our social arrangements.

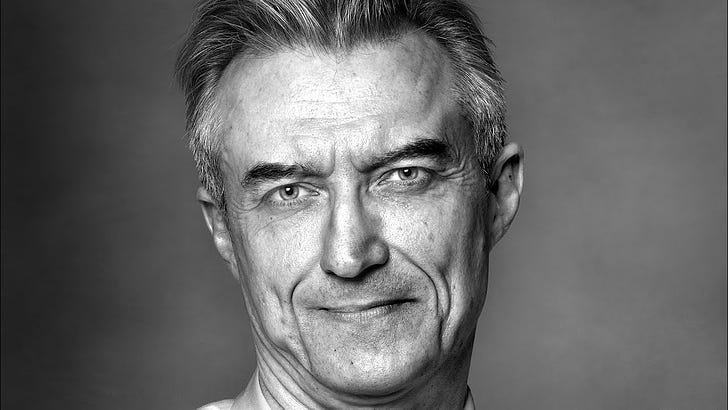

Have a look at this recent interview, with an American divorce attorney, on the subject of ‘love and marriage’:

He is articulate and funny, and makes a number of important and valuable observations. But his comments are indicative of a problem that is widespread in modern life: a tendency to understand marriage (and by extension family arrangements) in terms of moral ideals.

To somebody who is used to thinking about morality self-consciously in light of abstract principles, the critique of marriage comes naturally. Why, rationally speaking, would marriage be suited to modernity? Marriage, after all, was ‘invented’ (it’s a symptom of this style of thinking to imagine ancient customs as having at some point been ‘invented’) when people had a life expectancy of only 30 years, whereas now we can expect to reach 80 without breaking a sweat. Lifelong partnership makes much less sense when life is so long. And why would we consider marriage to be a suitable way to arrange relationships given that when it was ‘invented’ the circle of available mates was, for a given man or woman, in the region of the low dozens across the course of a lifetime, whereas now it is in the millions? Think of all the hookups, the Netflix-and-chill, that the modern young person is giving up by getting married, but which simply weren’t an option when marriage first came into being. Indeed, why would we need marriage in the first place, given that nowadays women do not need men in order to support themselves and can live perfectly secure lives independently, and given the support available to single mothers provided by the state?

Marriage is seen as essentially defunct, when considered in these terms. And the broader point, of course, is that it fails to justify its own existence in light of prevailing moral ideals - namely those concerning freedom, equality, the pursuit of happiness, and the application of reason. Marriage constrains freedom, is an institution of inequality, limits the potential to pursue pleasure, and does not make sense when considered objectively. It is therefore, to use the language of our friend the divorce attorney, an outmoded ‘technology’ and should be thrown on the scrap-heap. Pursuing virtue ‘as the crow flies’, we are only able to see the institution as an obstacle to be cleared on our flight to moral perfection.

A century or so ago, people would not generally have thought about marriage in these terms (avant-garde types such as HG Wells excepted). I do not mean this in the sense that they would have made the assessment about marriage’s usefulness as a ‘technology’ differently. I mean that they would not have considered ‘usefulness’ in light of moral ideals to be a comprehensible criterion for assessing the institution. This is because at that time people were much more used to an unreflecting, habitual understanding of morality: there was a right and a wrong, but those things basically corresponded to a prevailing sentiment rather than any percieved relationship to well-reasoned principle. One got married because it was right to do so, and it was wrong to raise a child out of wedlock. And there the matter mostly began and ended, give or take some biblical references. The morality of marriage exhibited itself in adherence to custom, and did not justify itself in reference to ideals. Most marriages lasted because divorce was shameful and it was very important for the status of children to have both parents around. And that was that.

Morality manifesting itself through mere habit has its many drawbacks, as we know. Nobody sensible can make the claim that marriage as it was understood and practiced in 1923, or 1823, was perfect or without its injustices. And there is no doubt that women were at the sharp end of those injustices for the most part, nor that gay people were denied opportunities for long-term contentment that were open for straight people to enjoy. There is no case to be made that unreflecting application of mere habit is good in itself, and often it’s helpful to apply some of the insights that can be derived from reasoned consideration of moral principle.

But we now see, in very clear terms, the negative consequences that follow when moral thinking takes on a purely abstract, principled character - when every institution has to be self-consciously reconciled to the existence of prevailing moral precepts. Pursuing a vision of perfection - freedom, equality, reason - we cast marriage aside, and congratulate ourselves that we are abandoning the irrationality of our benighted ancestors. But this blinds us to the grim truth that we have no idea what to put in its place: ‘lacking habits of moral behaviour, we have fallen back upon moral opinions as a substitute’, and discovered that they are poor substitutes indeed.

The biggest single casualty of the replacement of moral behaviour by moral opinion is the concept of ‘staying together for the kids’ - something that was once probably routinely practiced (few people would have openly admit this, of course), and which is at heart a truly ennobling sacrifice of personal happiness in the name of meeting more important needs. Now the idea that one might reconcile oneself to a ‘mediocre’ relationship in the name of familial stability is widely pilloried; the result is that family life has, in the words of the Instituted for Fiscal Studies (IFS), become ‘more diverse, fragile and complex’. And since children in ‘diverse, fragile and complex’ families are ‘far more likely to do worse in school, earn lower incomes, be unemployed, work in less prestigious jobs, experience psychological problems during their childhood and adulthood, pass through the criminal system, and suffer alcohol and drug addiction’ the consequences of the death of ‘staying together for the kids’ are grave.

At the same time, the number of children being born itself is plummeting, such that demographic decline shifts towards demographic crisis. And this is no doubt related. Having lost the habit of seeing marriage as an almost inevitable feature of adulthood, and thinking of it instead as a kind of capstone to a successful middle-class lifestyle, the timeframe within which traditional family formation can start is becoming ever more truncated. Less time in which to make babies in the context of a stable, committed relationship means fewer babies. And the population pyramid continues on its merry way to inversion, with results that will be disastrous.

In other words, while we are certain at all times what to think about marriage (it’s old fashioned claptrap), we struggle to come up with the foggiest idea about what we should do instead - what kind of relationships we should have, how we should bring up children, and ultimately whether we should even be doing either of those things at all. Over 50 years after the enactment of the Divorce Act 1969 we still don’t have a clue - and with every passing year we travel yet further away from the moral habits which once sustained us.

There are plenty of well-meaning suggestions being made about how to resurrect marriage and childbirth as matters of policy (tax breaks, subsidised mortgages, cheap loans, student debt forgiveness, and so on). And given the position in which we find ourselves, these may be options worth pursuing - certainly it is not possible to imagine a sudden and spontaneous resurrection of 1950s marriage norms among the population at large (even there were widespread agreement that this would be desirable, which there clearly isn’t).

But these technical fixes will themselves be strongly resisted, because of course they are impossible to reconcile with the moral ideals which dominate our thinking. When the Tory MP Danny Kruger made the claim earlier this year that ‘normative families’ were the basis for a secure society, he was not only widely criticised by the usual suspects, but undermined by his own Prime Minister (a man with an impeccably normative family), who made it clear that this was ‘not the government’s view’. We know why: because to imply that the ‘normative family’ is superior to ‘diverse, fragile and complex’ modes of family life is to contravene the abstract principle of equality which our moral idealism holds so dear.

The problem, in other words, is not how we think about marriage per se, but our predilection for thinking of ‘the moral life’ as exclusively a vision of applied perfection rather than an adherence to the received wisdom of our ancestors leavened by reason. It will take a lot for us to abandon that predilection, but recognising its character and the problems it causes us at least starts us down the path to reimagination. This does not, and should not, mean a willed embrace of unreasoning customary prejudices. Rather, it simply means accepting that reasoned reflection on moral ideals is a helpful corrective to the excesses of traditionalism rather than a blueprint for morality in its own right - and that treating is as such a blueprint is the cause of many of our deepest problems.

That life expectancy used to be around 30 is an old misunderstanding. Statistically it is true; but what people fail to grasp is that it was because so many people died in infancy or childhood. Once past the age of, say, 12 or 15, all the evidence is that hunter-gatherers have always had about the same lifespan as "civilised" folk. (Perhaps slightly longer, in view of their healthier way of living).

So the "life expectancy" argument fails outright; by the age at which people might get married, their life expectancy was little different from ours. And in fact the huge toll of childhood disease and accident is a powerful argument in favour of attentive, supportive parenthood.

Another insightful reflection, David - thank you! Part of the problem here is that 'marriage', much as 'religion', has ceased to be a a descriptor of something positive (as 'religion' was for Tolstoy), but a stick with which to beat at any and all 'tradition'. The question of marriage today is the question of whether you are capable of making a promise. What you promise can be 'diverse and complex' - but if we cannot even make a promise, our problems go far deeper than the issues with marriage.