On classical liberals and conservatives, and Gene Wolfe's revolutionary Tolkienism

The 'new right' thinks it opposes liberalism; it is wrong

Why don’t we lighten things up a little bit around here and discuss the relationship between classical liberalism (or libertarianism, if you prefer) and conservatism?

The right is on both sides of the Atlantic currently undergoing a messy divorce from the economic policies of the past. On the one hand, all of the energy among American conservatives is on the ‘America first’ side of the fence; trade liberalisation and open borders aren’t even within spitting distance of the Overton window. On the other, British conservatives appear to have decided that, whatever the rights and wrongs of the matter, Thatcherism as an electoral force simply could not be deader. This has been accompanied by what one might call a ‘cultural pivot’ in both countries, and across the developed world in general. The right is everywhere re-embracing some of its traditional attachments, such as to the nation and family, and extricating itself from the wreckage of technocratic globalism. As a result, it is becoming rather ambivalent towards the concept of ‘freedom’, and frequently even flirts with describing itself as ‘post-liberal’.

Accompanying this, we see a lot of time and effort devoted, in conservative circles, to rubbishing liberalism and libertarianism - usually along tried-and-tested lines. Liberalism, we are told, prioritises rights over responsibilities, fostering self-centredness and encouraging atomisation. In prioritising freedom, it encourages license, even depravity. It dissolves social and familial bonds. It is morally vacuous, elevating ‘being left alone’ to the level of supreme virtue. It is wishy-washy and lacking in the courage to make judgments. It is misguidedly rationalistic, insisting on dubious grounds that people are capable of debating and reasoning their way to Dworkinian ‘right answers’. And so on.

These criticisms all have something to them. But I want to suggest in this essay that classical liberalism’s critics are guilty of taking in isolation what can only be understood as part of a matrix of developments - i.e. that what the ‘new’ (or ‘dissident’) right thinks it hates about liberalism is really a hatred for the clumsy amalgamation of two radically different ways of understanding the relationship between the state and the individual which emerged in early modernity.

The English political philosopher, Michael Oakeshott, helps cast light on this. In his masterpiece, On Human Conduct, Oakeshott describes modernity as imposing freedom upon the population. Whereas in medieval society everybody more or less knew their place in the social order and was swathed in social rights and obligations as a consequence, we moderns are born into an ostensibly much more fluid set of arrangements, whether we like it or not. Some people respond to this positively. Well equipped by background, education, status and also innate character, they see freedom as a good in itself and embrace the possibilities (and pitfalls) that it offers. Others, though, are discomfited by freedom and even fear it. Much happier living the life of a ‘conscript assured of his dinner’, they prefer security, predictability and communality to the instability and riskiness of genuine liberty. Oakeshott called the former, freedom-embracing type the ‘individual’, and the latter, security-loving type the ‘individual manqué’; there are no guesses for working out where his own sympathies lay, but it is probably important to bear in mind that he seemed to be setting up these two character types as competing philosophical ideals rather than a method for categorising actual human beings.

At the heart of the distinction between the individual and individual manqué is an attitude to risk. The individual pursues freedom in full awareness and acceptance of the fact that his own mistakes, or sheer bad luck, will have negative consequences. He takes this as the price for which liberty is bought; to be truly free is to live without take-backs. The individual-manqué takes the diametrically opposite view - risk is to be diminished as much as possible, and freedom is worth sacrificing in order to realise that goal. What matters is security.

To grossly oversimplify Oakeshott’s argument, these two different archetypes have informed the way in which the modern state has developed. On the one hand, there have been political forces that have insisted on constraining the state in order to preserve liberty. And on the other there have been political forces that have insisted on deploying the power of the state to achieve security. These can basically be thought of as the forces of liberalism and communalism respectively - while recognising that obviously both of these bodies of thought are much more complicated and nuanced than the crude picture I am sketching out here (and also making clear that Oakeshott himself was very careful to avoid using terms like ‘liberalism’ and ‘communalism’ for reasons that will have to be left to a future post).

The modern State, of course, inhabits the tension between these two poles. Out of one side of its mouth, it claims to govern in as limited a way as possible. And on the other, it claims to intervene in society at every turn in order to make life materially and morally better for the population. And thus, as any reader will recognise, we are governed - on the one hand constantly being told that we are free, but on the other being carefully micromanaged at a very granular level, right down to the most humdrum aspects of our daily lives, such as being required to sort rubbish into the correct types for recycling or being ‘nudged’ away from buying sugary drinks. In this way, we see Oakeshott’s basic dichotomy play out - with the modern State comprising a ‘ramshackle’ (to use his word) compromise between the political imperatives of the individual and the individual manqué.

While these two imperatives do exist in a state of tension, however, they also feed off each other and can even be seen in many circumstances to be mutually supportive. Perhaps the most obvious illustration of this is the family. Liberalism, for obvious reasons, can be said to emphasise freedom of choice in marriage - and hence, it follows, in the breakup of marriages too. In this sense, we have seen the preferences of the Oakeshottian individual play out in the last 60 or 70 years. And yet the consequence of this liberalisation has been the creation of a great mass of people - single parents (almost always mothers) and vulnerable children (almost always effectively fatherless) - who themselves are forced by circumstances to lean heavily on the, admittedly meagre, security offered by the State - to become, that is, individual manqués, not out of choice but out of necessity. At the same time, though, these unfortunate people, who are themselves reduced to almost complete reliance on the State’s largesse, in practice often live the lives of libertine caricatures, freely making and breaking relationships in often very chaotic and messy circumstances. In short, in some aspects of their lives they become almost libertarian extremists - not so much individual manqués as individuals to the nth degree.

The tension between liberalism and communalism therefore resolves itself in ways that are often highly ‘productive’, as a Foucauldian would put it - or, to the rest of us, create a vicious circle. The human subject of liberalism, ostensibly the political movement of the individuals, often in fact becomes highly reliant on the State to rescue it from freedom’s results. And at the same time, the human subject of the communalist State, who is shaped at every turn to be a passive recipient of the blessings bestowed upon him by public bodies, in practice comes to embrace an individualism that is almost anarchic. What we have, in other words, is a ‘toxic’ (to use that much overused word) mixture by which the individual’s insistence on freedom is combined with the individual manqué’s insistence on security such that freedom become untethered from its consequences and takes flight to very dark and undesirable places.

It is this vicious circle that I think conservative critics of liberalism really take issue with, and to this extent I entirely agree with them. But it hardly needs emphasising that this problem (probably the most profound problem of our age), is not fairly one that can be laid at the door of liberalism per se. Rather, it is the fault of the intellectual and political webs in which liberal values have found themselves becoming enmeshed. In short, if the Oakeshottian individuals had had their way and our system of law and governance gave freedom its due - that is, if it were generally accepted that the necessary corollary of freedom is facing up to the genuine risk of failure and misfortune - the problem would very quickly have resolved itself. Freedom’s excesses would never have come to fruition, because the consequences would have been too dire.

In a world without a cradle-to-grave social welfare system, in other words, people would take much more seriously decisions about whether or not to marry or have children, and would take their commitments concomitantly more seriously as a corollary of that. In such a world, people would naturally embed themselves in the lives of their extended families, churches and communities, because that would be their source of support when times became hard. ‘Moral eccentrics’, as Oakeshott would have put it, would be less extreme, because they would have to retain ties with the people around them in order to maintain social stability. And, of course, the excesses of the market would also be tamed, because there would be no corporate safety net, either; risk would have consequences, and finance would be conservative in the small ‘c’ sense and prudent with its investments. I also happen to think that many of our other social ills - drug use, addictions of other kinds, compulsive screen use, and so on - would be ameliorated (though surely not eliminated) in such a society too, because the incentives would flow towards more helpful contributions to family and community in the absence of a State-sponsored safety net. This would certainly not be a paradise, or a utopia - and it would have its costs, some of them severe. But it would be a society much more in keeping with the values which conservatives hold dear than our current predicament affords.

There is, in other words, a way for liberalism to set itself up in a virtuous circle with the imperative of communalism - or, to put it another way, for the individuals and individual manqués to reconcile themselves to each other in a much more constructive fashion than they have come to do in the modern State. In insisting on the State doing less, in other words, a full-bodied commitment to classical liberal values ends up allowing civil society, families and religious institutions to truly flourish - and thus aligns closely with what are commonly supposed too be communal values too. Ironically, insisting on freedom (and on the consequences of freedom) therefore ushers in a much thicker and more robust - and more authentic - sense of society than the State ever could.

Classical liberalism, in other words, at the end of the day inheres in a basic insistence that individuals should be governed as lightly as possible. But this, properly understood, also means that they should face the natural consequences of their own freely-exercised choice; and this can only have consequences which can properly be labelled conservative.

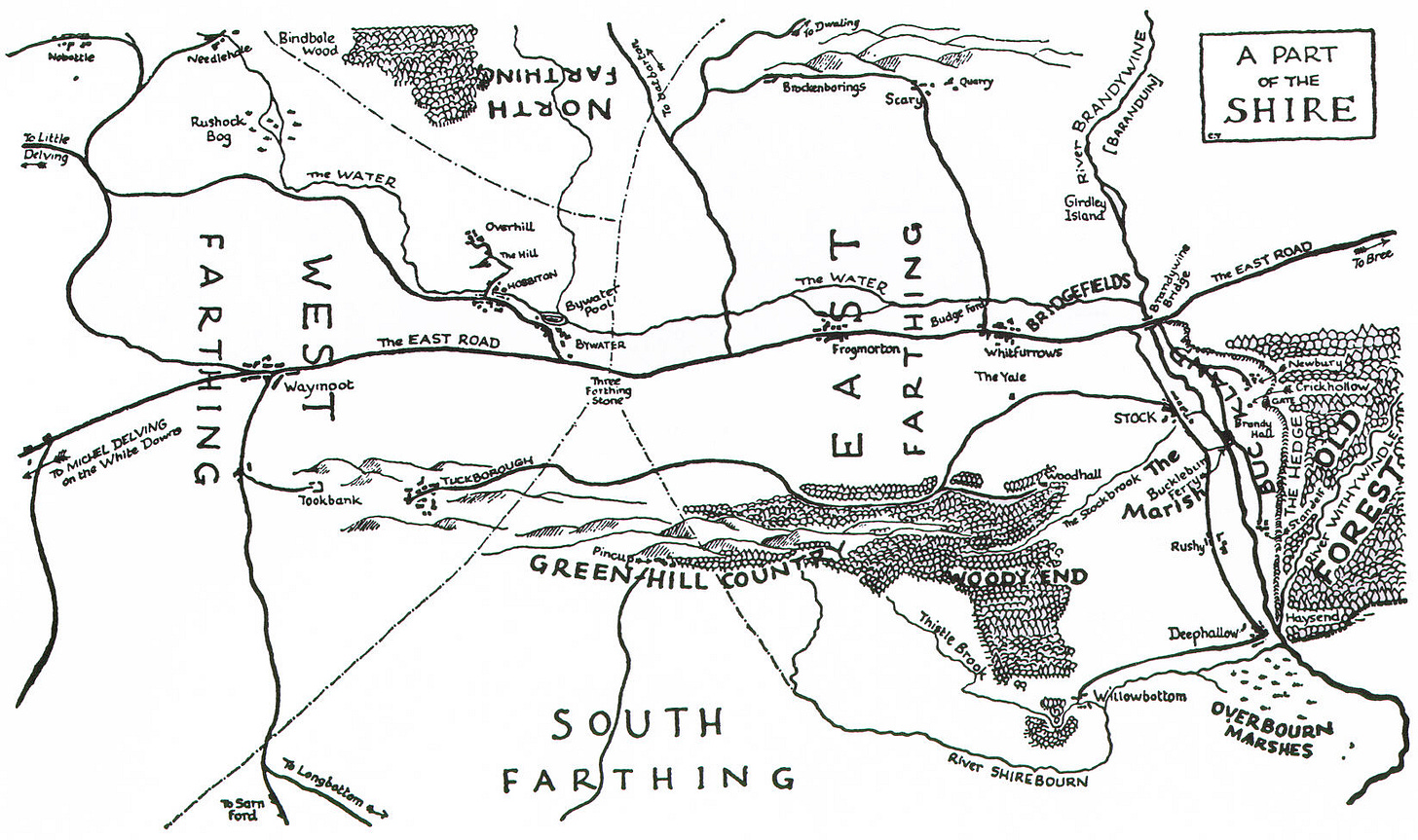

The writer Gene Wolfe, himself a paleoconservative Catholic convert, helps shed light on this in his 2001 essay on Tolkien, ‘The Best Introduction to the Mountains’. In it, he succinctly lays out the case for the association between small-State liberalism and conservatism (though he does not quite put it in those terms), locating the relationship between the two in what he calls ‘folk law’. For Wolfe, Tolkien’s philosophical contribution in The Lord of the Rings (and it is, indeed, properly so-called), is in identifying the strength of ‘the West’ not in Greek or Roman civilisation but in the ‘neighbour-love and settled customary goodness of the Shire’, where ‘everyone stood shoulder-to-shoulder because everyone lived by the same changeless rules, and everyone knew what those rules were’.

The heart of this ‘settled customary goodness’ is the fact that it is indeed customary. Contrasting it with the ‘pestilent swarm’ of special-interest legislators who impose their will upon the rest of us in the name of public service (but in fact crave only power), Wolfe calls this kind of system one in which ‘laws [are] few and just, simple, permanent, and familiar to everyone’. Because they are of general application, they are by definition not enacted in the service of any one group, but simply apply to all. And as a consequence, they cannot be corrupted in the service of political projects, but merely recognise the common sense goodness of properly socialised human beings, and allow that common sense goodness to perpetuate itself.

There is here a clear echo of what Oakeshott himself labelled a ‘civil association’ - that is, a society in which law acts only as a kind of ‘grammar’ informing social interactions and choices otherwise freely determined, and is not deployed for any specific interventionist cause. This, Oakeshott said, was the only form of morally justifiable arrangement of law, society and governance (another issue that will have to wait for a future post); in any case there is no denying that it suggests a combination of both the classical liberal insistence on the restrained State, and the conservative emphasis on social responsibility and public duty, in a mutually reinforcing relationship. And it is a relationship that one can indeed still glimpse here and there around the world in communities which have managed to come through the past 50 years of social upheaval relatively unscathed - certainly anybody familiar with rural England or Japan will have seen (and envied) the results of it, even in the highly attenuated and degraded form in which it nowadays subsists.

Crucially, Wolfe describes the values that lie at the heart of this nexus as ‘freedom, love of neighbour, and personal responsibility’. This is the important point on which to close. There is no antagonism between freedom, love of neighbour and responsibility - quite the opposite. Being free means facing the consequences of one’s actions. This has to encourage responsibility and mutually supportive relationships with those around one. It is not, then, that having too much freedom is the problem our societies face, or that liberalism is to blame. It is that we have broken the necessary connection between freedom and consequences - and urgently need to discover how to mend it. Indeed, I think it is more realistic than pessimistic to observe that we are quite far advanced along the road to the point of being forced to do so.

You mention that without the welfare state people may change their views on marriage and children. I think that the welfare state changes all our economic decision making, effectively resulting in the government making a uniform decision that applies to all of us and probably benefits the state. If we had to provide for our own health care and pensions we would have to save more and we would not be spending on holidays, cars, entrainment, technology, etc. I think it would slow down progress and give more thinking time about the benefits of some technology.

This is a brilliant and challenging essay that, as such, I feel will not travel. It is noteworthy that I am leaving the first comment, and more than a week has past. But on the positive side, it has found me, and that is at least something! Alas for you, I have to engage in this one quite heavily, so prepare for extensive critique, even though I am in great support of certain aspects of what you are laying out here.

"For Wolfe, Tolkien’s philosophical contribution in The Lord of the Rings (and it is, indeed, properly so-called), is in identifying the strength of ‘the West’ not in Greek or Roman civilisation but in the ‘neighbour-love and settled customary goodness of the Shire’, where ‘everyone stood shoulder-to-shoulder because everyone lived by the same changeless rules, and everyone knew what those rules were’."

So many tangents here I shall have to pick just a few! Firstly, it is absolutely the case that Tolkien's legendarium (not just The Lord of the Rings) is a philosophical contribution, but like C.S. Lewis, Tolkien's philosophy moves entirely within Christian monarchy. Both authors (perhaps only when viewed retrospectively) end up defending royalty through ideals that still just about applied at the beginning of the twentieth century, but now are very difficult for anyone to take seriously.

Does this weaken Tolkien's contribution? I'm uncertain. It certainly does not help his ideas travel philosophically, and it is noteworthy that the Peter Jackson adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, and its prequel (erroneously called The Hobbit - The Hobbit categorically not being a prequel to The Lord of the Rings) are about telling battle stories. Only a sliver of the philosophical content survives, and in the case of The Hobbit movies (which are in actuality an adaptation of the appendices to The Lord of the Rings) very little of Tolkien's ethos survives conversion.

Michael Moorcock, who was very influential for me, and highly supportive of my philosophical work (few have been!), was vehemently opposed to Tolkien's writings. I feel I owe Moorcock a representation of his position here, which is that Tolkien represents the city - and by extension the working class - in the form of the armies of Orcs, and in effect takes the side of the English rural middle class against the working class. While it is certainly possible to argue against Moorcock's objection here, I believe he is correct to have ascribed to Tolkien a rose-tinted view of the English (possibly British - difficulties here...) rural town. It is perhaps fairer to suggest that Tolkien's late-breaking opposition to industrialisation is the source of the hostility, but it is logical to see this as leading to a prejudice against the working class. Fascinatingly, Moorcock's literary (rather than fantasy) writing manages to show a similarly rose-tinted view of working class London - although he also, unlike Tolkien, deconstructs this mythology as well (especially in Mother London and King of the City).

I raise this contrast here because I personally think it is problematic to idolise the Shire in this way. One only has to think of the dreary conformity that runs as a theme within the bookends to The Hobbit, which makes Bilbo into an outsider because he decides to act in a way that is not respectable. With all the good will in the world, I could not take the Shire as an ideal of any kind, while still acknowledging that it functions in this way for Tolkien, and that readings like those you report here are certainly both available and credible.

"The heart of this ‘settled customary goodness’ is the fact that it is indeed customary."

And herein perhaps lies the problem...

"And it is a relationship that one can indeed still glimpse here and there around the world in communities which have managed to come through the past 50 years of social upheaval relatively unscathed - certainly anybody familiar with rural England or Japan will have seen (and envied) the results of it, even in the highly attenuated and degraded form in which it nowadays subsists."

I am familiar with rural England (I grew up on the Isle of Wight) and have some familiarity with Japan, since a good friend of mine lived there for many years. In both, there is a stifling conformity that undercuts any attempt to idealise these cultures, one that again Tolkien himself successfully depicts in The Hobbit. This conformity is even more severe in Japan. I admire the way Japan has held onto various aspects of its traditional culture - but I also must report my friends utter infuriation with the refusal of Japanese people to 'rock the boat', even in situations they would recognise as out of order. There is simultaneously something great and something terrible about these two cultures you single out. I don't want to take too strong a line against this here, because I do think that there is a maintenance of community in these contexts that is worthy of praise - but I could not, even with the greatest of squints, pretend that there are not commensurate problems as well.

"There is here a clear echo of what Oakeshott himself labelled a ‘civil association’ - that is, a society in which law acts only as a kind of ‘grammar’ informing social interactions and choices otherwise freely determined, and is not deployed for any specific interventionist cause. This, Oakeshott said, was the only form of morally justifiable arrangement of law, society and governance..."

Aye, but herein lies the problem, because what is currently happening is that our cultural 'producers' (to borrow Foucault so you don't have to!), of which Google is perhaps the most significant player, are managing to install a grammar that has been eagerly eaten up by the generation just reaching adulthood. They in turn have deployed this grammar in an interventionist manner (they may have been aided, in this regard, by US academics, whom I fear have abandoned the very idea of a university). The culture wars we are all acutely aware of right now flow out from this dynamic. This generation has affiliated via a network of robots, and are uninterested in the effect this has had on them, empowered as they are by youth's utter certainty. Given the ubiquity of robot intermediaries, it is difficult to see how to break this pattern. As a father of three boys, it is a problem that troubles me greatly.

In this regard, it is worth noting that I do have one hope: I read to them. Amongst other things, I read them The Hobbit. I doubt I will read them The Lord of the Rings, but I do have a copy of the BBC radio adaptation, which may well get an airing. In a situation whereby cultural power accumulates in those who control what is permitted to propagate within the walled kingdom of the internet, books from the civilisations we have lost may represent the last, best hope for resurrecting civil associations.

Many thanks for stimulating these remarks, and apologies for the length of this comment, but I lack the time to make it shorter.

With unlimited love and respect,

Chris.