Still only half-right after all these years

There may not be such a thing as purely free speech, but it still needs defending

Free speech is currently under attack from both left and right. And the critics, though they would no doubt hotly deny it, basically agree on why it’s bad. For the left, it crates space in which nasties like ‘hate’ and ‘disinformation’ are given free rein, and must therefore be vigorously curtailed. And for the right, it creates space in which nasties like ‘cultural Marxism’ and ‘woke propaganda’ are given free rein, and, er, must therefore be vigorously curtailed. Oddly, this all really just goes back to JS Mill. Speech should be free, we all agree, as long as it isn’t harming anyone. It’s just that ‘harm’ is a floating signifier which can mean almost anything, and therefore serves as a freestanding justification for restricting almost any speech at all.

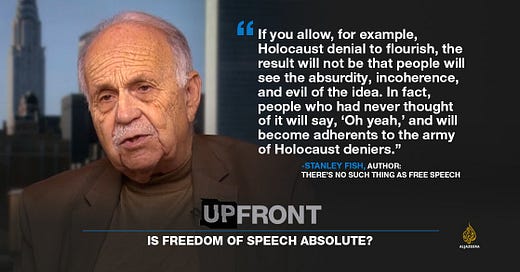

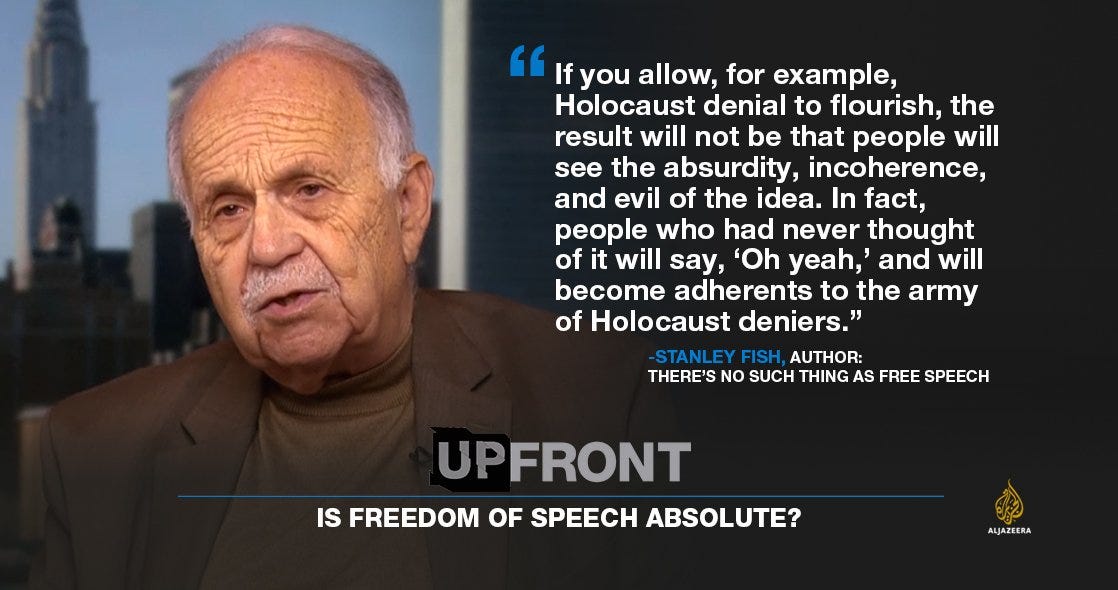

This was all accounted for by the American literary theorist-cum-legal philosopher, Stanley Fish. According to what he told us in 1993, ‘There is no such thing as free speech’. What there is instead is politics, and power - with law following after. The ones in control of the institutions, in other words, get to decide what is acceptable speech and what isn’t (very often on the basis of nebulous concepts like ‘harm’), and then also get to decide what the law permits or restricts. What we think of as ‘free speech’ is just what we remains to be said once unacceptable speech has been ruled out.

Hence, for example, in the 1950s, people were much more free than nowadays to express the view that there are innate differences between the sexes. But they were much less free to express positive opinions about homosexuality. Now, the balance has shifted, and people are nowadays free to say almost anything they like about sexual mores, but it is considered unacceptable - even bigoted - to suggest that there are material differences between men and women. This is not because there has been a free debate in the ‘marketplace of ideas’ and the best side won; it is because there was a battle of perspectives and different people with different ideas are now in charge of the culture. (Or, to put it less conspiratorially, because the people who dominate the institutions these days happen to have imbibed different cultural values to those which prevailed in the 1950s.) ‘Free speech,’ as Fish therfore summarises, ‘is not an independent value, but a political prize’.

Fish is one of the sharpest minds of his generation and probably the most trenchant of liberalism’s critics since Carl Schmitt (somebody with whom he had some things in common - more on that later). His work is important to engage with on those grounds alone. And, to give the devil his due, he was clearly onto something here. Carry out a quick thought experiment: do you think there are any political views that a school teacher should be prohibited from expressing to children? Deep down inside, it is likely that you do. Which views count as being beyond the pale will vary - perhaps it will be out-and-out racism, perhaps it will be the opinion that drag queen story hour is a great idea, perhaps it will be views for or against transitioning children, perhaps it will be revolutionary Marxism, perhaps it will be views about controlling immigration, perhaps it will be the idea that the age of consent should be abolished - but it will vary based on your values, and values are fundamentally political. (Sometimes free speech advocates will say things like, ‘People should be free to say whatever they like within the bounds of the law’, overlooking the fact that it is legislators - i.e. politicians, who have values - who make law.) The question of where the border between acceptable-and-therefore-free speech and unacceptable-therefore-unfree speech lies is therefore itself fundamentally a question of politics, not unmoving constitutional principle.

Fish was obviously at least partly right about this. (Ronald Dworkin, his famous sparring partner, had much to say against it, but for reasons of space I’ll simply suggest picking up a secondhand copy of Doing What Comes Naturally, in which Fish guts and skins Dworkin and has the rest of him for breakfast.) And his conclusion is seductive. This is, simply, that we should not merely recognise but embrace the fact that the border between acceptable and unacceptable speech derives from politics - and, indeed, that we should seek to win control of where it lies in order to ensure that it is our own values that shape the landscape of acceptable public discourse.

This, however, leads us to dark places. And this is where Schmitt comes in. Schmitt, as everybody with internet access now seems to know, insisted that, when the chips were down, liberalism is a complete sham. When people really care about an issue, they don’t want to extend the courtesy of good faith debate to the other side, and they don’t even care about abstract reasoning. They simply want their values, the ones they hold dear, to triumph - and to squash the opposition. Liberalism does its best to cloak all this in purportedly holding to high-falutin’ principles like ‘freedom of speech’ and democracy. But at a time of crisis that all goes down the toilet. What matters is making sure it is the views of you and your friends which win out over your enemies.

Fish would not have endorsed Schmitt’s personal values, of course. But ultimately the argument is similar. Both thinkers depict society as riven by deep and irreconcilable conflicts between competing worldviews. These conflicts are often hidden, but they never disappear, and have a way of coming to the surface at times of tension or crisis. And the idea that these worldviews can rub alongside one another is foolishness. They tolerate one another only when they have to. And when people holding a particular worldview control institutions, they have no qualms about imposing their views on everybody else.

Defenders of liberalism have to accept that this picture is often descriptively accurate. And an interesting illustration comes in the form of the curious recent case of Mohammed Adil, and his treatment by the medical and judicial professions (working, as they often do, in concert).

Mr Adil is a surgeon who, between April and October 2020, made a number of YouTube videos alleging amongst other things that the Sars-CoV-2 virus did not exist; that the pandemic was foisted on the world by Israel working in cahoots with the US and UK; that the pandemic was a ploy to impose a ‘new world order’; that Bill Gates was deliberately infecting people in order to sell vaccines; and a by-now fairly familiar litany of similar assertions. In 2022, the Medical Practitioners’ Tribunal of the General Medical Council, which is the only body to maintain a comprehensive register of medical practitioners in the UK, decided that the making and uploading of these videos amounted to misconduct and impaired Mr Adil’s fitness to practice, and duly suspended him from the register (effectively making him unable to work) for 6 months.

Last week, the High Court handed down judgment in the case of Adil v GMC [2023] EWHC 797 (Admin), his unsuccessful appeal (on freedom of speech grounds) for judicial review of the GMC Tribunal’s decision. The court had little truck with the substance of the appeal, and basically ratified every element of the Tribunal’s own reasoning. The judgment is worth reading all the same, because of what it shows about the views of the upper echelons of society (including of course high-ranking judges and medical practitioners) with regard to the boundaries of free expression and where they should lie, and how it serves to go some of the way to proving Fish’s (and Schmitt’s) critique.

The Tribunal had considered Mr Adil, whose videos ‘ran counter to the public health messages being disseminated at the time’, to have acted to ‘undermine public health’. Moreover, since the messages in those videos were ‘contrary to widely accepted medical opinion’ the Tribunal had also been of the view that they undermined confidence in the medical profession - with the implication of course being that this would also harm public safety.

The judge, Swift J, duly went through the motions of applying article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the relevant portion of which being the following:

The exercise of [free expression], since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of…public safety [and] for the protection of health.

In other words, the question was whether Mr Adil’s suspension was a proportionate interference with his Convention rights, given that it was done in the purported interests of public safety and the protection of health. Was it necessary in those terms?

There is much to be said about the judgment in this regard, but for our current purposes it suffices to describe Swift J’s own view, which was that this was a situation in which a body of medical expert was suspending one of its own members for saying things which it ‘knew’ to be likely to undermine public health and faith in medicine. In other words, this was a circumstance in which he ought simply to pay due deference to the considered views of professionals about a matter firmly in their own bailiwick, and derive his assessment of ‘necessity’ and hence proportionality from there.

But anyone with two brain cells knows that this is not really what was going on in this case. Adil v GMC is not a considered or nuanced application of the ECHR, or medical expertise, to facts. Rather, it is mere confirmation that, when it comes to Covid-19, there are certain views which polite society simply holds to be beyond the pale. We all know what these views are. And we all know what happens to people who openly express them.

The crucial section of the judgement is therefore paragraphs [32] to [34]. Here, Swift J first makes the following comments:

It is not difficult to think of examples of matters on which doctors’ opinions on medical matters will differ. The simple fact that one opinion could legitimately be described as “widely accepted” ought not, of itself, provide a sufficient justification for professional discipline of medical practitioners who held a different opinion. In many instances, there will be obvious value in legitimate discussion of different or conflicting medical hypotheses, or of whether received wisdom should be revisited. Disciplinary action in such circumstances could amount to an unjustified interference with article 10 rights. Neither holding nor expressing an outlying opinion on a matter of professional practice ought to give rise to punishment, absent clear justification, for example where there is evidence of harm to patients or public health.

All perfectly reasonable of course, and nothing which any sensible person could disagree with (though let us flag, as an aside, that no evidence of harm to patients or public health was ever adduced in this case). But, Swift J then goes on:

In its Determination on Impairment the Tribunal described what Mr Adil had said as promotion and perpetration of conspiracy theories. At paragraph 72 (set out above), the Tribunal referred to his comments as going “... far beyond helpful legitimate comment into the realms of scaremongering conspiracy theories”. That was an accurate description of the matter. There is a clear qualitative difference between claims of the sort made by Mr Adil – for example, that the SARS-CoV-2 virus did not exist – and situations where the issue might concern competing opinions on other such as the measures that should be taken to combat or reduce the spread of a disease.

In other words, there is an arena within which reasonable people - and reasonable medical experts - can disagree. But there are certain opinions which simply ought not to be held. And when somebody expresses those opinions, freedom of expression goes out of the window.

We all know that, in stating the matter in these terms, Swift J was providing an accurate summary of the way our society views the subject of freedom of expression in general - i.e. that it is okay so far as it goes, but poses problems when the chips are down and best, in those circumstances, to be ignored. And we all know the types of things that one could say (not just with respect to Covid-19) that would immediately put one within the realm in which freedom of expression no longer applies - indeed, in which one can be made subject to all manner of ‘restrictions and penalties’ much worse than those faced by Mr Adil.

In other words, Adil v GMC is firmly located in Stanley Fish’s world, where there is an arena of acceptable speech in which reasonable people are permitted to disagree, and an arena of unacceptable speech which must not be uttered. The High Court was simply recognising where the border between acceptable and unacceptable speech when it comes to Covid-19 lies. And, it hardly needs pointing out, that did not reflect fundamental constitutional principle, or even just existing legal rules, but rather where power in our society lies and what the views of the powerful are. Our political, cultural and educational institutions took a particular view about Covid, and what it was acceptable and unacceptable to say about it. And the law, as we see in Adil v GMC, merely reflects and enforces that.

What, then, are those who would defend liberalism to do? The title of this post makes clear that Fish is half-right, but also half-wrong. There is no doubt that ‘actually existing’ liberalism often looks like the rather bleak picture that he (and Schmitt) was painting for us. And, seen from the perspective of 2023, his description of society as being continually rent by irreconcilable differences that cannot be resolved through open debate in the ‘marketplace of ideas’ but only through the seizure of institutional power seems prophetic.

But, despite his own insistence that he wished to ‘issue no clarion calls’, this actually now has to serve as a call to rhetorical arms. In 1993, public debate in the developed world was probably at the peak of its civility - and faith in liberal values, in the afterglow of victory in the Cold War, was likewise probably at its zenith. (It is difficult now, for those of us who were alive at the time, to remember how different the texture of life was then - and, of course, impossible for those who are younger than the age of 30.) It made a kind of sense for Fish to paint himself, given the context, as a reasonable voice of caution against liberal tub-thumping triumphalism.

That, however, is emphatically not the position in which we now find ourselves. Fish is probably right that there is no such thing as completely free speech, and that the phrase really means ‘whatever is left after those in control of the institutions have ruled out what they consider to be unacceptable’. But that arena can be comparatively big or small. We all of us (well, almost all of us - Fish himself has his doubts) recognise that in the last decade it has been getting much, much smaller - and at a rather alarming rate. And this has been accompanied by a widespread decline in faith in liberal values - freedom of speech being chief among them.

I don’t think I’m going out on a limb in suggesting that the relationship between those two variables is causal. And, by the same token, this implies that a rediscovery of faith in liberal values can make the arena in which speech is allowed to be free to grow in size. We cannot, as Fish shows us, ever achieve a circumstance in which speech is genuinely untrammelled, and nor should we wish to. But we can aspire to ensure that, generally speaking, our institutions err on the side of allowing more speech rather than less, and to regulate expression more lightly than they do heavily. Yes, as Fish would correctly point out, that comes with the risk that forms of speech will proliferate which themselves will drown out the speech of others. But that risk is dwarfed by the clear and present danger associated with the alternative.

And, despite himself, Fish reminds us that this aspiration is achievable. The whole point of his essay, in the end, is that, as he himself put it, ‘it is not that there are no choices to make or means of making them; it is just that the choices as well as the means are inextricable from the din and confusion of partisan struggle’. Anybody with eyes to see is now painfully aware that this is right. And those of us who care about preserving the essence of liberalism need to face up to the fact that we are in not so much a partisan struggle as a partisan dogfight. It is one we need to win - to ensure that it is our values (good faith, reasonable discussion and debate, small government, neighbourliness, civility, freedom, and pluralism) that are the ones which shape the political landscape in the future.

To give a final example to conclude, the Daily Express recently reported that a Conservative MP, James Sunderland, had been disinvited from appearing at an event at the University of Reading due to his views about the necessity of restricting immigration. The spokesman for the university’s Political Association gave the reason for this as being that ‘we feel it would be inappropriate to bring in somebody whose views [on] immigration conflict with the ethos of the society’. This is, again, a happening straight from Stanley Fish’s world. But it need not have played out this way. Mr Sunderland was only disinvited because a (presumably relatively small) coterie of students were in charge of the society and decided they wanted the arena of acceptable speech to be small. What we need to do is to be more persuasive - and more canny - in ensuring that those in charge are of a mind to make that arena bigger instead. And we can all see the consequences of failing to do so: paucity of debate, atrophication of ideas, badly educated young people, and the celebration of prejudice.

There may not be such a thing as pure freedom of speech, in other words. But we still need to defend it where we can, because the alternative to doing so - i.e. that we continue merrily down the path to technocratic authoritarianism - is far worse.

As I've written, everyone quickly picks up on what is the "current thing" - which is the "authorized narrative." At the top of our ruler pyramid, we have nefarious actors creating bogus narratives for their own benefit. But beneath this level, we have 99 percent of the population that is afraid to go against the accepted narrative. For good reason - they know if they express contrarian views or challenge the authorized narrative, they are going to experience unpleasant consequences.

Nice to see Fish getting an airing... he was essential reading for a certain generation of philosophers, but swiftly fell off the back of the academic apple cart. I must (indulgently) note that I used to write essays like this but I gave it up because nobody cared: my existing readership leaned strongly left, and they could not even see that we had reached a crisis point in free speech. It is therefore both pleasing to see you getting some traction with this one, and also raises some concerns. It might be a warning that we have lost the political centre since the gap has become so wide.