The Devil's Reason

On the government of the world

The devil’s own tragedy is he is the author of nothing and architect of empty spaces.

-Sebastian Barry

Cast the net of your memory into our collective cultural sea and it may trawl up a gigantic hit from the mid 90s, titled ‘What if God was one of us?’ Well, in this post, I want to ask, ‘What if Satan was one of us - and what if he had a political philosophy?’

Admittedly this is a less catchy title for a song. And I should issue a disclaimer: no belief in Satan, or God, is required in order to understand or accept what follows here. Rather, our focus is on Satan as one of the central, indeed foundational symbols of Western culture - a figure who has occupied a crucial role in the way in which we have understood ourselves for many centuries. In particular, our interest is in the understanding of Satan as being the ruler or ‘prince’ of the world and what that signifies about the nature of government in modernity. My argument - and you will have to forgive me for being a trifle provocative - is that the way we have conceived of the devil helps to understand ourselves still, and that by describing the path we are on politically as Satanic we can actually plot out our direction of travel a little more clearly. Again, as we shall see, this hinges in particular on the role of the world in what I will advisedly call our political theology. Faith in God (or Satan for that matter) is, I once more reassure you, entirely optional.

Let us begin, then, with two straightforward premises. The first is that we live in a politically secular age, by which I mean an age in which politics is understood to have no relationship whatsoever to matters of the spiritual, theological, sacred, or divine. The second is that it is natural that since religious thinkers (and throughout this post I am generally referring to thinkers in the Christian tradition), consider matters of the spiritual, theological, sacred and divine to be of the most profound importance, they should have since time immemorial imagined the categorical rejection of such matters to be itself a source of evil. The figure of Satan, as the personification of evil, has therefore to Christian thinkers very often been understood to have the goal of proving that matters of the spiritual, theological, sacred and divine are an irrelevance, and with encouraging mankind to ideed reject those things as meaningless and irrational. Hence, to resort to Hollywood cliche, ‘the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist’; Satanism consists in the complete rejection of not just God, but of spirituality as such - and the concomitant embracing of the world as the essence of existence.

One does not have to believe that secularism is evil in order to understand this association, and therefore to grasp Satan’s semiotic role in the Christian tradition as a symbol of irreligion or unbelief. And this means that is useful, in understanding secular politics, to examine how our that tradition has conceptualised Satan - not in order to label secular politics itself as Satanic, but in order to discern what it is that religious believers have concluded about what politics shorn of any religious aspect really means. Another, simpler, way of putting this is that theologians in the West have been preoccupied with what loss of faith in the Judeo-Christian God has meant for hundreds if not thousands of years, and it would be odd if that vast body of thought had not generated insights about what irreligion or secularism looks like when it is manifested politically.

We start our analysis proper, in other words, by picking a fight with GK Chesterton. It is not that ‘When men choose not to believe in God, they…then become capable of believing in anything’. Rather, it is that when faith in God is abandoned, people tend towards known patterns of thought. They don’t come to believe in ‘anything’ - they come to believe, time and again, in certain things which are generally the same. And thinkers in the Judaeo-Christian tradition, who have devoted an awful lot of time and energy to explicating why abandonment of faith in God is bad, have a fairly clear idea what those repetitive patterns of thought entail. This gives us a rich source of ideas from which to draw in analysing what secular politics ultimately entails.

The Devil and the World

To frame our discussion of political secularism, it is worth briefly turning to the words of somebody who is most decidedly on the periphery of the Christian tradition, the English occultist and comic-book author Alan Moore. Here is a link to a conference Q&A with Moore, during which the subject Satan comes up. I choose this not because it is a particularly orthodox interpretation of anything, but because it is clearly, amusingly and interestingly stated, and because the idea that the devil speaks in a broad Northamptonshire burr is really just too perfect.

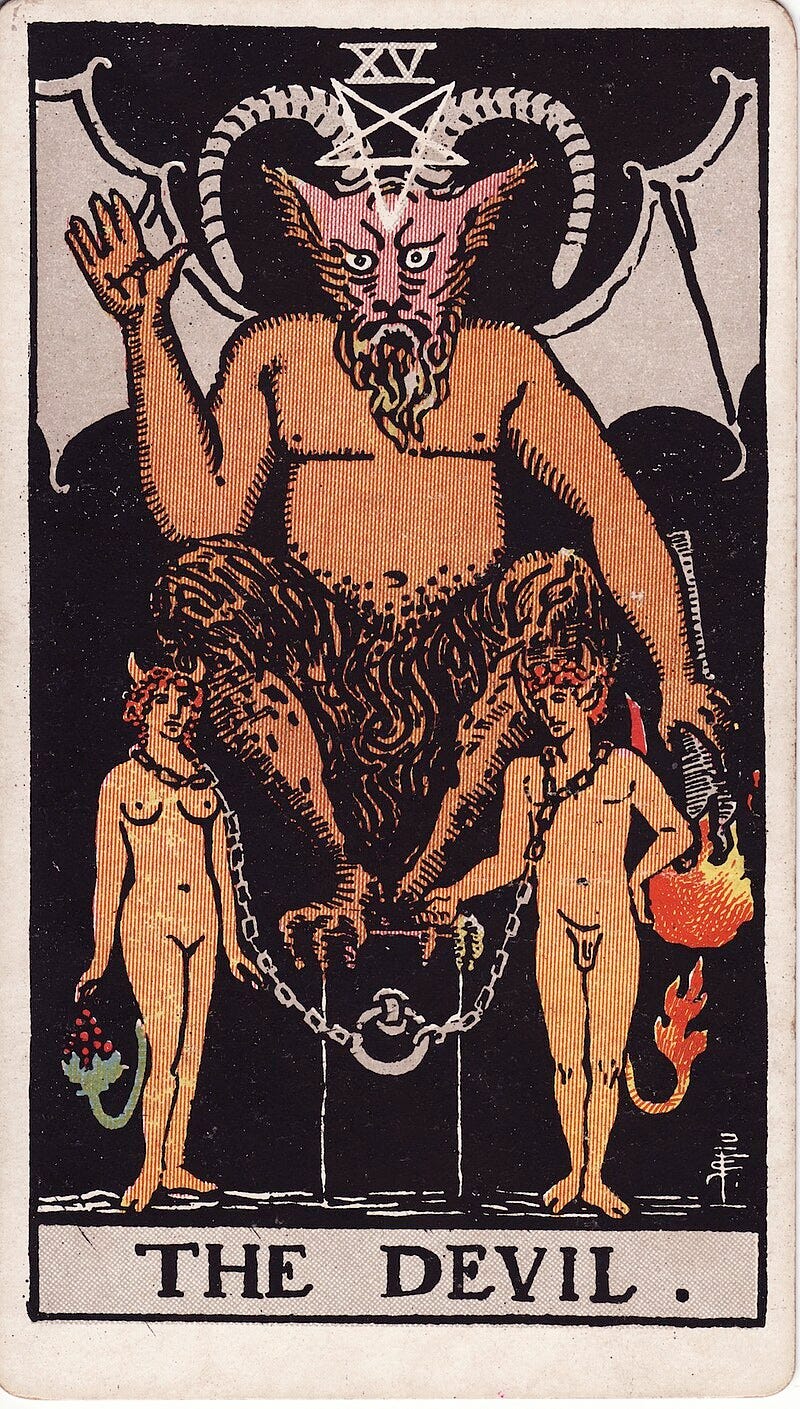

Moore invites us to examine the tarot card depicted at the top of this post, drawn from Alistair Crowley’s ‘Thoth’ deck, and to concentrate in particular on the upside-down pentagram in the devil’s forehead. Why is it upside down? Well, the pentagram, Moore tells us, when it is the proper way up, is supposed to represent the rulership of spirit (the quintessence, or fifth element) over the four elements of the material world (earth, wind, fire and water). It symbolises the fundamental superiority of the spiritual over the physical, with spirit being the single point at the top of the pentagram, and the other elements being the four points of the star situated below it. Inverted, Moore goes on, the pentagram means the converse: spirit, the single point down at the bottom, means nothing, is situated beneath the material world, and hence is ruled and indeed dominated by it - the material world is everything. Moore goes on:

[It’s] pretty much encoded in that upside-down pentacle [sic]…What you’re saying if you invert the pentacle is that the material world is in complete domination. And in fact spirit is so low down that it might as well not even exist. That the material world is all there is. And this is the message of the devil on the tarot card. What he is saying is…

‘Look, all of that [spiritual] stuff, it doesn’t exist. It’s not real. There is only me. There is only the material world. And if you actually bow down and worship me, I can give you all sorts of rewards….You know, money, you’d like some money, wouldn’t you? And you’d like lots of material possessions. So put aside all of these thoughts of spirit, or any kind of personal advancement of consciousness, because that’s all just a delusion. That’s a fairy tale. Worship me and I’ll reward you. Or, if you give me any trouble, just think about all the things that I could do to you. I could take away your money, couldn’t I? How would you like poverty? And what about ill-health? This material world is all my domain.’

And that is the whole point of that parable [sic] in the Bible about ‘Get behind me, Satan’. It’s a kind of hologram. [The material world] is all that it can offer and that is all that it can threaten. And that is a truly Satanic view of reality. It’s a dictionary definition of Satanism as far as I’m concerned: that the material world is everything, that we are no more than our physical bodies…

Satan, in other words, in this reading, is a radically secularising force. His role is to undermine mankind’s relationship with God by insisting that our existence, and the world which we inhabit, is purely material (i.e. that it has no spiritual element at all), and his idealised end is that our only concerns should relate to the world, reified as the central feature of our existence. We must lose interest in the divine, and the world itself must become the repository for all of our hopes, fears, joys and woes; in the absence of the spiritual, the temporal realm will become the only game in town. And we will therefore begin to define ourselves and the meaning of our existence exclusively in relation to the material or physical plane, rather than the divine - which we will cease to believe exists at all.

Since - I suppose this ought to go without saying - the secularisation of politics also inheres in the rejection of the spiritual and an insistent focus on the temporal or material, the connection between the symbol of Satan and the secularisation of politics becomes very clear when framed in this way. I repeat, this is not to call secular politics Satanic; it is rather to emphasise Satan’s position as a kind of semiotic device enabling us to understand the meaning of the loss of, and rejection of, religious faith and the spiritual dimension of human existence as such - including in the political sphere.

The Political Philosophy of Satan

The doctrine that ‘the material world is everything [and] that we are no more than our physical bodies’ clearly has profound political implications. In previous posts I have, following Michel Foucault and Leo Strauss among many others, explained the history of political thought as being characterised by an important break in the figure of Machiavelli - who heralded the dawning of a new morning in which politics would be shorn from theology, and the two would never be reunited. Man would be governed no longer on the basis of theological justifications, but temporal ones - and therefore government itself would become exclusively interested in the doing of things in the material world: manipulating it, measuring it, discovering it, mastering it, commanding it. It would have no spiritual element, and in fact would in part define itself by turning its face against such matters. It would take a long time (centuries in fact) for this separation of religion and politics to play out, but play out it ultimately would, and that process would be irrevocable.

You will now see why it is that Machiavelli was so widely despised in his day (despite being so widely read) and why his reputation became so bad that even today his name remains synonymous with political evil. It is not because he was so amoral (blithely advocating, for example, the murder of children where politically expedient); it is because his contemporary readers understood perfectly well the implications of his texts. His conception of government was secular, not divine. And the necessary implication is that government’s role with respect to the temporal realm is not merely to reflect the way in which God rules over creation - by making and enforcing simple, clear, and immutable laws - but rather to ‘govern’ the material world as such.

This has consequences which go very deep. Because once ‘governing’ the world has become the aim, there ends all constraint on government’s ambition. If the aim of government is precisely to govern the material world, then what realm of life ought to remain untouched by government’s fingertips? What flaws ought not to be mended, ills cured, injustices rectified, impurities purged, risks averted, wounds healed? There can be none, and the only limits on what government can do will therefore be physical, economical or technical - with the scale of government’s ambition inexorably expanding as our physical, economical and technical capabilities develop.

Regular readers of this substack will be familiar with this analysis, but may very well not have thought about the implications for the world itself. Government which relies for its own justification on the fact that it governs is also reliant on the ability to conceive of the world in a certain way, and to concieve of the relationship between humanity and the world in a certain way, too. A world which is only material, and in which there is nothing that is of significance spiritually or theologically, is a world, in Foucault’s words, ‘purged of its prodigies, marvels, and signs’. It is a world which we can, if we simply try hard enough and have the right level of technical skill, know in every detail, measure with perfect accuracy, encompass within our minds, and therefore control and command as we see fit. It is a world that can in principle be mastered by mankind - and the result of course is an understanding of mankind’s ultimate goal as the mastery the world itself, achieved through what by definition can only be our own expertise and power.

If Satan were to have a political philosophy, then, this would be its ideal: government of the world, without end; government all the way down; government to the very last detail - perfect government of everything. And everything that government would do in practical terms would in some degree or other gesture towards that totalising end point. And it is no accident, I hope you can see, that secular government should have precisely the same trajectory. This is not because Satan is literally at the helm, but because this is the necessary implication of government unleashed from theological constraint.

Satanic Themes in Modern Government

Satan’s political philosophy is concerned with the government of ‘the world’, then, and this observation yields important insights into the nature of secular politics.

In the first place, let us recall one of the most striking apparances of Satan in the Bible, in which we find him, at the beginning of the Book of Job, coming together with the angels to meet with God. According to the King James version (Job 1:7):

And the Lord said unto Satan, Whence comest thou? Then Satan answered the Lord, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it.

Satan is a wanderer then, for whom the whole world is a place to ‘go to and fro’ and ‘walk up and down’ in as he wishes. His frame of action, it follows, is not bounded. And why should it be? Since the world is after all just a place like any other - albeit a very big one - then what is stopping him? What is stopping anyone?

There is in other words no limit on the size and scope of secular government except for those imposed by ‘the world’ itself. And this in turn has two sets of connotations. On the one hand, since the world indisputably contains absolutely all material phenomena, and since human beings are in this sense just as much part of the world as rocks, trees or puddles, there can exist no borders or barriers to government’s purview in respect of human life - nothing in that regard is off the table. Family life, childrearing, sexual intimacy, physical health, mental health, nutrition and food, even the realm of the genetic, even the realm of thought: all of it is contained in the world, and therefore all of it should in principle be governable. And on the other hand, since the world is government’s object, government’s ambition should indeed literally be global - it will not only refuse to limit itself geographically, but will consider geographical limits to be contemptuous and will seek at every turn to transcend them.

Second, Satan does not just wander through the world, but exerts dominion over it. The devil is, as we have already seen, its ‘prince’ or ‘ruler’ (as Jesus himself puts it). And hence he can command it, or bestow its contents as gifts, accordingly:

And the devil, taking Him up onto a high mountain, showed unto Him all the kingdoms of the world in a moment of time. And the devil said unto Him, ‘All this power will I give Thee, and the glory of them; for this has been delivered unto me, and to whomsoever I will, I give it. If Thou therefore wilt worship me, all shall be Thine.’ (Luke 4:5-7).

Secular government, then, is likewise for command of the world’s resources - and for their rearrangement and redistribution as government sees fit. It owns everything, and can dispense what it owns to whoever it chooses accordingly. It follows, necessarily, that those who live in the world own nothing - and are reliant on government for their status. They might, if they are lucky and if their face fits, gain ‘power’ and ‘glory’, but these are things that are bestowed, rather than earned; there is no independent or autonomous path to either, and the only route to advancement is through government itself.

Third, Satan reifies knowledge as the means by which immortality is achieved. To come to his most famous appearance of all (from Genesis 3):

Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made. And he said unto the woman, ‘Yea, hath God said, “Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden”?’

And the woman said unto the serpent, ‘We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden, but of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God hath said, “Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall ye touch it, lest ye die.”’

And the serpent said unto the woman, ‘Ye shall not surely die; for God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.’

The message here is clear: if one wishes to be a god - to indeed supplant God - then one’s eyes must be opened; one must see and know all. Secular government then must concern itself above all else with knowing the world in all of its detail and all of its fullness - it must measure the world; it must number, catalogue and categorise the world’s contents; it must somehow quantify the unquantifiable and intangible; it must process; it must calculate; it must render everything, to use James C Scott’s arresting term, ‘legible’. There is nothing too small or too insignificant that can on that basis escape being known - and no part of human life that can stand outside the scope of government’s knowledge.

Governing Like a Devil

These three themes of Satanic political philosopy - its refusal to acknowledge limits, its drive to mastery or dominion, and its understanding of knowledge as being at the root of power - taken together are suggestive of a governing style that seeks to ultimately exert total control over the world, and everything in it.

And it should be no surprise then to discover that when the political sphere has been thoroughly secularised, this governing style tends to assert itself - not, to repeat, because Satan is literally behind that process, but because it follows logically from what the secularisation of politics really means in respect of government’s justification, and ends.

Hence secular government sees no limits, and so it cannot understand the argument that some sphere of life or other is not amenable to being governed - nor that borders or jurisdictions should be any prima facie reason why the project of government as such should be disrupted or hindered. Secular government seeks to exert dominion over the world, which it purports to own, and so it does not accept property rights as a barrier to its projects of redistribution and benevolent gifting. And secular government is preoccupied with the idea that it must be in a position to measure, number, and surveil every aspect of its possession - and indeed to model the future so that it can ‘know’ that in advance too - so that it can better and more completely rule. It is characterised not by an instinct for what is the right thing to do in a particular circumstances, but by statistical reasons for doing so, whether because some policy or other has been modelled to have a particular effect on some metric or other, or because it is thought likely to have an influence on poll numbers, and so on.

You will of course be deeply familiar with this picture, because it daily plays out before our very eyes. No better example springs to mind than the approach taken during the era of the lockdowns, when governments around the world, almost without exception, took it upon themselves in a coordinated, globalised way to regulate every last aspect of their populations’ lives (down even to whether they were allowed to have sex, or hug a dying family member, or attend a funeral); to declare at the sweep of a pen whether any particular individual member of the population was permitted to work, study, recieve taxpayer support, or run their business; and to obsessively and pedantically ‘measure’ and model every element of the phenomenon - from ‘case’ numbers and ‘excess deaths’ to the ‘R number’ and to the daily figures for ‘jabs in arms’. And the same philosophy of course lies behind all of the grand governmental projects of the day - to command the climate, to ‘rewild’ nature, to achieve perfect equality, to eliminate ‘misinformation’, and so on.

But of course it also happens daily in more mundane form; this is simply the way in which modern government is performed. You will have your own favourite illustration, but my own (which I have written about before) is that of supervised teeth-brushing in schools. No area of life, remember, can be outside of government’s purview, and no government redistribution of taxpayers’ resources is ever unjustified - and, since ‘modelling’ has shown that supervised teeth-brushing will have the desired effect on the rates of tooth decay, it simply must and will be done. Never mind the fact that it will involve the deployment of considerable public resource, and never mind the fact that it will produce generations of youngsters who are so infantilised that even their dental hygeine will be contingent on the benevolence of the State. To repeat my earlier observation, the logical end point of the trajectory that we are on is the perfect government of everything - government all the way down, or, if you prefer, government to the hilt. There is no critique of the expansion of the scope of government that ever really gains traction, because expansion is simply in secular government’s nature - it is inherent to it. Therefore there is nothing that one can say against the supervised teeth-brushing policy that can withstand the weight of the logic that impels it. And what is true in this regard is true across the piece.

I Know I Believe in Nothing, But It Is My Nothing

This is where we are, then, and this is where we are going. But it is important, in bringing these thoughts to a close, to note another important implication of what (to once again re-emphasise) I have called the semiotic role that Satan plays in our understanding of the secular.

This is that if there is one thing that Satan cannot do, it definitionally is to create. Satan can know, he can possess, he can distribute, he can manipulate, he can measure - but he cannot make. This is a central theme in the works of the great Christian thinkers of the twentieth century, and one which I think finds its clearest and best expression in JRR Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, in the description of the demonic Ungoliant:

But she had disowned her Master, desiring to be mistress of her own lust, taking all things to herself to feed her emptiness; and she fled to the south…Thence she had crept towards the light of the Blessed Realm; for she hungered for light and hated it.

In a ravine she lived, and took shape as a spider of monstrous form, weaving her black webs in a cleft of the mountains. There she sucked up all light that she could find, and spun it forth again in dark nets of strangling gloom, until no light more could come to her abode; and she was famished.

Note the central message here: evil does not itself make anything, but can only hunger after what is created, suck it all up, and use it to spin into lesser material. It can in short corrupt what is created, and thereby sustain itself for a time, but this is a process of diminishing returns which ultimately always ends in ‘famishment’. There is no true nourishment there - just a kind of ineffectual parasitism. That is where Satanism finally leads, in the Christian framing; for all of the devil’s grandiloquence and for all that he aspires to supplant God, he is (to use Moore’s word) in essence a mere ‘hologram’ and, of course, in that regard much less ‘real’ and much more of a fairy tale than the spiritual understanding of reality which he claims to subvert. In the end his power is a sham, a nothing, a cul-de-sac, and the material world for which he advocates itself an empty shell.

And hence one will notice that for all of secular government’s vaunting ambition, and for all that it is capable of marshalling the resources which it claims to own to genuinely awesome effect (think of the sheer power that was exerted to mobilise the Nazi, Soviet and American war machines of 1941-45, or the way in which the wealth of our societies is funnelled, with concentrated force, to the pet political projects of the day), it can never create, but only appropriate, redistribute, manipulate, manage, and rearrange whatever it is that society produces. And it always does so to lesser positive consequence than would have been achieved it had left well alone. It would be an exaggeration to liken government too closely to a demonic spider sucking the light out of society and spinning it into ‘dark nets of strangling gloom’ (though I can think of a great many ways in which current government policy could aptly be described with that metaphor) but the important point is that even where it can be said to be necessary or useful, it only ever takes from, rather than gives to, society in aggregate.

As I have previously sought to explain, then, the most important thing to understand about secular government, and modernity as such, is that there is - I mean this literally - no future in it. It does not create, but only appropriates and corrupts, and corruption cannot last. We head then towards famishment, notwithstanding the highly unlikely prospect of a reintegration of the spiritual and political, and this is something with which secular modern people will some day have to reckon. It is not something that can be avoided forever.

Deeply interesting essay, and brave.

"The devil’s own tragedy is he is the author of nothing and architect of empty spaces."

This quote strikes a chord in me; When considering contemporary art, music or design/achitecture I'm often left thinking "but ... there's nothing there!" There is an emptiness, a hollowness to much of what is 'created' -- or rather: generated. Like interacting with an AI chat-bot, you realize that there is nothing there, it's empty -- it has no soul.

A powerful piece of writing, whipping along the Satan metaphor soundly.

And yet although I agree that governments whirl away without reflection on the long march towards a totalitarian Utopia (and this is undesirable for the being of the mere mortals caught up in the gears).

But Satan is an abstraction that ignores other useful fictions, other enlightening metaphors... you could just as easily have written:

"Hence theocratic government sees no limits, and so it cannot understand the argument that some sphere of life or other is not amenable to being governed - nor that borders or jurisdictions should be any prima facie reason why the project of government as such should be disrupted or hindered. "

This would perhaps resonate more with readers if they lived in a theocratic society like modern Iran, for instance. Or perhaps, historically, look at the great size of the Abbotsbury tithe barn for an insight into earlier theocratic influence in the 14th century. Reliance on non-material worldviews is just as consequential whether the team is Godly or Demonic.

So the common element is perhaps not the demonic metaphors but the rather less semiotic obviousness of the nature of governments. Governments *must* manage - and that this leads to greater and greater control on the long path to a desired outcome, whether Heaven, Hell, or Utopia.