The first thing we do, let's remove all the screens

'Digital skills' will take care of themselves; it's the other skills we need to worry about

We all know that there are few characters in life more plaintive and foolish than the school music or literature teacher who has decided to teach their subject through reference to modern, ‘popular’ trends - abandoning Bach and Shakespeare for Stormzy and Rupi Kaur. But the sheer lameness of the spectacle is not the only thing that is wrong with such misguided endeavours. For most children, from most backgrounds, school is the one chance they have in their entire lives to be exposed to their rich cultural heritage and familiarise themselves with its quest for transcendance. It is criminally wasteful therefore to devote school time to subjects which the kids will learn about anyway soon enough. Knowledge of Stormzy will take care of itself; that’ll be imbibed through osmosis. School should be about the introduction of ideas that would otherwise remain forever inaccessible.

Just as this is true regarding the substance of what is learned, however, so it is true for the process of learning itself. There is a widespread idea in education and policy circles that it is important for schools and universities to teach ‘digital skills’ to pupils and students, and that this ought to be done through the medium of digital tech. The theory would be that, since youngsters will grow up in what is inevitably referred to as an ‘increasingly digital world’, it is important for them to know how to navigate the technology in question. Hence iPads in the classroom; vast swathes of PCs cluttering open spaces at universities; homework performed on laptops.

This, however, is the ‘skills’ equivalent of substituting Ed Sheeran for Glenn Gould in music class. Look around you, at the young people you know, and the others you casually interact with. Does it seem to you that they have great difficulties interacting with digital technology? Are they strongly characterised by a lack of familiarity with gadgets and gizmos? Or would you agree with me in concluding that, if anything, they could probably do with spending a little bit less time hunched over and peering into a screen?

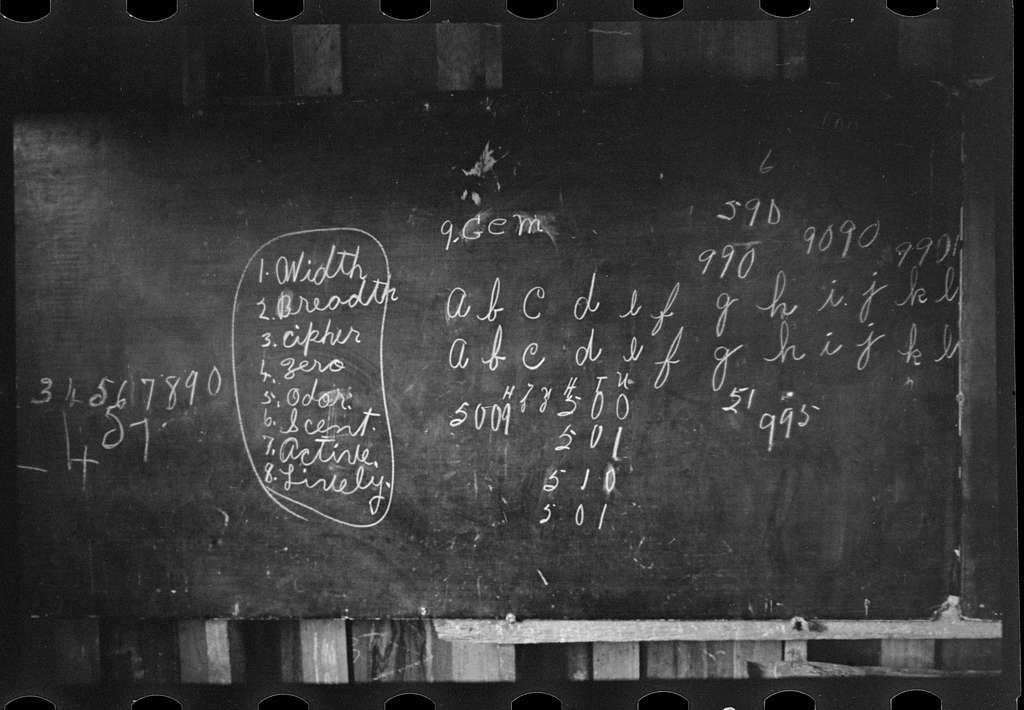

The truth, of course, is that the learning of ‘digital skills’ is - like knowledge of pop music - something that children nowadays pick up naturally. It’s not as though there is any incentive for manufacturers of digital technology to make their products difficult to interact with, and in any case most young people now marinade in the stuff so thoroughly they genuinely find it difficult to cope unless there is a screen of some kind close at hand. Our society, in other words, faces precisely the opposite of a digital skills deficit: vast swathes of young people growing up with no skills at all other than digital ones - no social skills, no verbal or written communication skills, no reading skills, no concentration skills, no practical skills. What should education therefore concern itself with? Reinforcing this trend? Or offering to pupils and students the opportunity to free themselves from the yoke of technology and interact with the world around them in purely physical, tangible ways?

We have become very used to thinking about education in instrumental terms - so much so that I think the ship of ‘education for its own sake’ has probably sailed. But granting that education is now primarily valued in terms of its practical usefulness, we should be thinking much harder about the type of usefulness which we want education to provide, and the types of things that we think it will be useful to learn. Teaching students about stuff which they will know about anyway in the fullness of time is to render the exercise redundant even in instrumental terms; if we’ve given up on trying to pass down our intellectual and cultural heritage to the young, the least we can do is provide them with ‘value added’ which they wouldn’t otherwise gain for themselves. I humbly suggest therefore that it’s time to chuck the PCs and tablets out of the window and blow the cobwebs off the stationary cupboard, so that we can provide our young people with the opportunity to think in ways that to them will seem utterly fresh and invigorating, being unmediated by the screens with which they otherwise spend almost every waking moment of their lives.

I couldn't agree more with your point of view, David! From what I hear (I have my sources) schools have suffered a cultural hijacking, largely in the direction of what's fashionable. As you say, it is increasingly assumed that everything must be done through computers - although the "skills" acquired are usually very narrow and restrictive: Microsoft Windows and perhaps smart phones.

Forty years ago, when I worked for a leading multinational computer firm, I witnessed an astonishing transformation. One year I was the despised "techy", the chap who knew machine code, assembly language, and compiled languages; understood how an operating system worked; and could even explain the intricacies of the file system. (Although I was surprised to note that, even after I had laid it all out in the simplest terms, my audience would claim to be utterly mystified).

Among managers, one of the basic marks of superiority was to know nothing about computers, software, or how they worked. Bosses would boast that they had to have secretaries take dictation, as they could not stoop to anything so vulgar as typing. (One claimed not to "know how" to use a keyboard!)

And then... came the PC! Instead of big timesharing computers, each manager now had his or her own PC - and suddenly they became very deeply interested indeed. Within a few months, attitudes swung round by 180 degrees, and now I came across groups of bosses at the coffee machine or the water cooler exchanging tips on spreadsheet macros! (I wondered how much harm they would do through wrong formulae or obsolete rules). Now I was the outcast because I DIDN'T use PC applications.

Soon all the other familiar curses descended on us. No one could just stand up and explain something: no PowerPoint, no credibility. Huge and elaborate spreadsheets became festering heaps of writhing bugs and inconsistent assumptions - sometimes causing managers to make astonishing claims about financial numbers. ("Computer says...")

I couldn't agree more thatclassroom time should be devoted to studying the actual subjects in question. Too many teachers are struggling to master esoteric techniques that in no way improve their outcomes. Every minute wasted on fiddling with software is a minute not spent on sharing knowledge.

The problems with school systems run far deeper than this lazy and ill-conceived reliance on computers you justly criticise here, David. As for 'Stormzy versus Bach' - music is a tricky beast! I fondly remember the futility of one of my middle school teachers trying to get us into listening to classical compositions... But music appreciation is a habit, and music lessons in schools do not have the scope or reach to instil it.

I personally would think it entirely possible to take a grime or rap artist and teach music appreciation by exposing the practices behind it, and through their use of samples, show the deep lineage of music that connects Stormzy to the Bach concertos Glenn Gould was famed for performing. That schools today could not even contemplate a curriculum where such an endeavour was plausible to pursue is emblematic of the deeper problems with the entire framework of contemporary schooling.