The Intransigent Right in the Middle of the Century (Part Two): The Shepherd and the City

On the irrelevance of left against right, and the true division in politics

In my previous post in this series, I described an absurd delusion concerning ‘right-wing’ intellectuals that is prevalent among progressive commentators. In this fantasy, conservative thinkers, for all their irrelevance in the academy, somehow exert massive and baleful influence over practical politics - such, indeed, that they constitute a genuine threat to modernity itself. I explained that this is simply nonsense: conservative intellectuals exert almost no influence over anything whatsoever, and certainly not over the course of politics. Their work is by and large not read at universities and their ideas are not taught there, and the result is the almost total absence of those ideas from the educational experience of those going on to become teachers, civil servants, and indeed most categories of professional - not to mention political aides. This means that those ideas do not, in practical terms, matter much at all.

What is the point, then, of conservative or ‘right-wing’ intellectuals, and what should they be doing?

The answers to these questions, for reasons which will soon become clear, require us first to deal with the increasing irrelevance of the left-right divide. It is nowadays trite to comment that the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ have become obsolete; I half-agree with this analysis. It is true that the distinction between left and right is not currently really meaningful, and has simply become a shorthand for two teams (one might as well use the words ‘red’ and ‘blue’) who are fighting a culture war - a war which is all too real, but which has very little to do with what the words ‘left’ and ‘right’ have traditionally meant.

Those who advance this argument are therefore correct, but in a slightly misleading way: it has never really been the case that the fundamental division in politics is between ‘left’ and ‘right’. And here I can do no better than to cite our favourite member of the ‘Intransigent Right’, Michael Oakeshott, who wrote, all the way back in 1974:

Travellers have not always been scrupulous in reporting where their intellectual journeys have led them, and in recent times intelligent explorers on foot have been few on these journeys as on any others: the travellers prefer to go by air and at night, reaching their destinations in sleep. And the confusion has been increased by jokers of both persuasions who, in deference to the vulgar, have altered the signposts to read: Right, Left; Reaction, Progress; Stagnation, Development; Poverty, Affluence; Conservative, Liberal; Cul-de-Sac, Open Country; Liberty, Security; Authority, Liberty…And even totally irrelevant designations have been posted, such as: Democracy, Authoritarianism, Capitalism, Bureaucracy, Pluralism, Centralism, etc. And before now a whole generation of would-be travellers has awakened to find that one of these jokers has posted both the paths with the same inviting sign: Freedom, Jerusalem, or Cockaigne.

For Oakeshott, ‘left’ and ‘right’ were in other words simply different flavours of the same ice cream: leftists and rightists both imagine the state as a great ‘enterprise association’ which conscripts the population into grand projects to improve well-being (and woe betide anyone who disagrees). The differences between fascism and communism were therefore in his analysis almost cosmetic - in both cases the basic vision of what the state is was more or less the same - and both of these ideologies were simply extreme versions of what liberal democracies also seek to do. In the end, it is all about the state improving society across various metrics so as to increase its well-being. The only points of distinction are what exactly ‘well-being’ consists of and the path to getting there: for fascism, ethnic purity; for communism, classlessness and perfect redistribution; for liberal democracy, equality and freedom. (It is interesting that each was grasping towards ultimate homogeneity - a subject for a future post.)

Oakeshott was not entirely alone amongst 20th century theorists in thinking of things in this way. Michel Foucault, in various lectures and interviews given at almost exactly the same period, was also wont to deny the importance of any real left/right divide. He too made the point that fascism and communism were essentially manifestations of the same impulse: the drive to improve society through mobilising the power of the state (right down to the most ‘biopolitical’ elements - birth, death, diet, sex, etc.). And he also saw that the liberal democracies were basically on the same path; they simply pursued their biopolitical ends through methods that were much more diffuse and indirect.

In both cases, then, there was an awareness of there being a much deeper division in politics than the superficial separation of left from right. Fundamentally, the three great ideologies of the 20th century were nothing but variations on one master ideology in which the population is considered to be reliant upon the state to improve its material and moral conditions. Liberal democracy, it is important to emphasise, was much more benign than communism or fascism (Oakeshott and Foucault both hinted that they accepted it was the least bad option available to us), but the difference is one of degree, not one of kind.

What, then, was the true division in politics? Oakeshott and Foucault used very different terminology, but their ideas were similar. For Foucault, politics in the West had been characterised since the classical period by a tension between two ways of imagining the state, which he referred to at one stage, colourfully, as the ‘shepherd-flock game’ and the ‘city-citizen game’. In the former, the state is a shepherd watching over its flock, both individually and as a collective; like any shepherd, it knows every intimacy, every nuance, of the lives of its sheep, and takes full responsibility for their security - the quid pro quo being the abnegation of their independence (every sheep knows that ‘to have a will of its own’ is to have a ‘bad will’). In the latter, meanwhile, the state presides over a union of citizens joined together in shared bonds of loyalty to a particular way of life, whose chief interest is in maintaining coherence and stability (including territorial integrity) across time. Here, the state as such has no particular interest in the lives of its citizens - even whether any given individual one of them lives or dies. Its concern is rather the continued security of an existing mode of living.

Oakeshott refers to these two ways of imagining the state as teleocracy and nomocracy (‘rule of purposes’ versus ‘rule of rules’) respectively, and his description of them is almost identical to Foucault’s shepherd-flock and city-citizen games, with the additional emphasis on the latter being concerned above all with a shared commitment to law. For Oakeshott, the characteristic of nomocracy (the city-citizen state) is that its citizens are bonded together by adherence to the same set of norms of conduct - and only this. They are free to pursue their own ends, as long as this is done within the framework of a common ‘grammar’ of general rules. The characteristic of a teleocracy, on the other hand, is that the state requires its citizens, whether they like it or not, to participate in the grand project which it has set for them and itself.

What we have, then, is the existence of two different polarities. At one extreme, the state conceived as a shepherd, watching over every detail of the lives of the population, managing their interactions, and improving the ‘flock’ across various predetermined metrics. At the other extreme, the state as nothing but the administration of a system of rules which the citizens follow in their day-to-day affairs, and to which they are loyal, because it reflects their pre-existing sentiments, customs, and norms of conduct. This is the real division at the heart of politics; this is the chasm which underlies all of our political arguments. Here is Oakeshott:

In short, my contention is that the modern European political consciousness is a polarised consciousness, that these are its poles and that all other tensions (such as those indicated in the words ‘right’ or ‘left’ on in the alignments of political parties) are insignificant compared with this.

Oakeshott and Foucault were both at pains to emphasise that no ‘actually existing’ state has every fully embraced nomocracy or teleocracy. Real states are always a mixture of the two. This is inevitable, simply because there are different situations (both physical and conceptual) in which one or the other of these visions will be deemed to be more appropriate. The Second World War and its aftermath, for instance, was characterised by strong popular support for teleocratic impulses, and in a certain sense this was necessary and understandable. All depends on the circumstances.

However, both thinkers also saw the story of modernity as essentially one in which the state increasingly engages in the ‘shepherd-flock game’, or becomes more teleocratic, depending whose nomenclature one prefers. The arc of history appears in other words to bend towards a pastoral future in which the state manages every aspect of each individual citizen’s life, whether directly or indirectly, in the name of ‘what is best’ - and the individual sacrifices true autonomy in return for being the recipient of the state's ‘kindness’ (Foucault’s word).

And naturally, of course, this also means that the arc of history appears to bend away from nomocracy, the city-citizen game, in which the state simply instantiates a commitment to generalised laws deriving from the customs and moral sensibilities of the citizenry. As Foucault put it:

[Modern governance] is not a matter of imposing law on men, but of the disposition of things, that is to say, employing tactics rather than laws…I think this marks an important break…the end of government is internal to the things it directs; it is to be sought in the perfection, maximisation, or intensification of the processes it directs, and the instruments of government will become diverse tactics rather than laws.

It will not have gone unnoticed to you that this is a pretty accurate description of what has gone on now for a century or more, and what is currently happening before our very eyes in rapidly accelerating form. The idea that the Western state exists primarily to uphold a system of law that reflects the morality of the populace is laughably quaint; we are heading instead towards a teleocracy par excellence, and our lives increasingly resemble those of sheep under a shepherd’s care - guided, managed, cajoled and, where necessary, threatened in order that we, individually and collectively, help fulfil the overarching goals which the state has set for society. We are not permitted to challenge those goals (to do so is to spread ‘disinformation’ and peddle conspiracy theory), and we are not permitted even to question their underlying assumptions (to do so is to be ‘low information’, ‘bigoted’, ‘toxic’, and so on); for the sheep, remember, ‘having a will of one’s own’ is to have a ‘bad will’. Our role is to do as we are told, yes, that goes without saying; more importantly, we are to abnegate our very autonomy itself as inherently ‘problematic’.

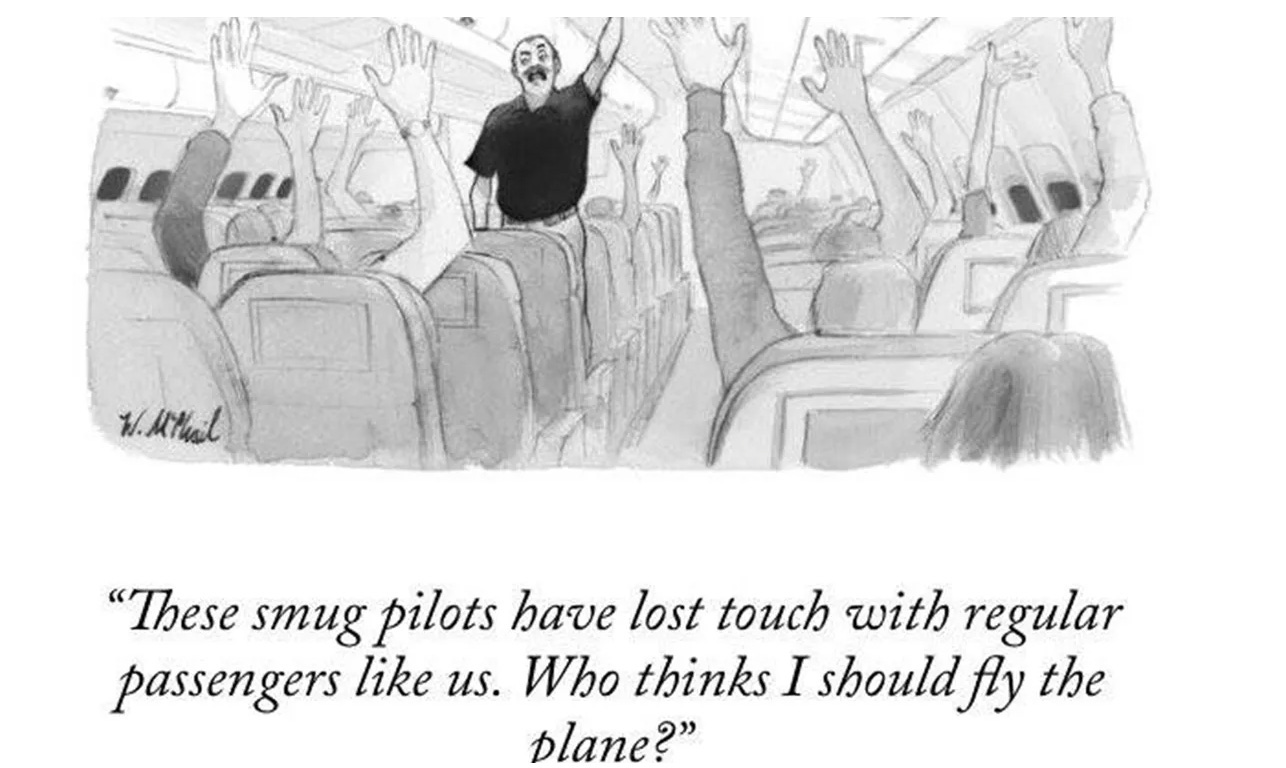

I know of no better illustration of the general embrace of teleocracy in our political life than this cartoon, printed by the New Yorker shortly after Donald Trump’s election victory in 2016:

Leave to one side your personal views about Donald Trump, and consider the underlying, highly apposite, message of the cartoon, and what it says about the mindset of both artist and audience: the state is like an aeroplane; the government is like a pilot. And, as pilot, its job is to get everybody safely to a particular destination, wherever that might be, deploying its vast expertise and training in order to do so. It knows what is best. It knows where to go. And it knows how to get there. The passengers, on the other hand, ignorant and helpless, have essentially one role - to sit passively and pliantly in their seats and wait. And, what is more, this is a role, the cartoon implies, that they should embrace. Any challenge mounted against the anointed authorities is per se illegitimate. Being an educated, intelligent, perceptive New Yorker reader means to accept that the state’s job is to get you to the collective destination safely - and to abnegate any decision-making role in the process whatsoever.

Our politics, in other words, is characterised not by a division between left and right, but between a commitment to teleocracy, the shepherd-flock game, on the one hand, and a residual commitment to nomocracy, the city-citizen game, on the other. The former is most prevalent within the institutions and the graduate class; the latter is largely the preserve of the lower-middle classes - the self-employed, the non-graduate, the tradesman and the farmer. The former sees the state as a project in which all of society is enlisted, guided by an elite class of experts who determine its targets and interim goals. The latter sees it as chiefly a commitment to maintaining law and order and social stability in the wider sense, in light of the existing mores and habits of its population. The former is interested in means and ends; the latter is concerned with upkeep and maintenance. The former sees society as an aeroplane, of which government is the pilot; the latter is more inclined to the analogy of a boat, floating free without a destination - its only purpose not to sink.

Seen in this way, many of the political conflicts which define our current period, and which seem to scramble the left-right dynamic, make a great deal more sense. Consider the culture war that is being played out across the Anglosphere regarding ‘wokeness’, which seems to see old left and new right united against the centre (or ‘new’ left - or is that the same thing?). It could in fact much more accurately be described as a dispute between those who embrace the idea that the state should make society more equal, versus those who think that the state’s role is only to make and enforce laws in a non-discriminatory way, and thus reflect the prevailing norms of daily conduct. Consider the subject of immigration, which does not pit left against right so much as it forces a confrontation between those who imagine the state as a grand project to promote well-being, and those who imagine it as a commitment to maintaining the stability of an existing way of life. And consider our contemporary anxieties about the education of the young, defined not by class conflict as it once might have been, but rather by the gulf between those who think the role of the teacher is to mould the young in light of a vision of perfection, or ‘merely’ to pass on learning from one generation to the next.

Everywhere, that is, we see the chief distinction as being between a vision of an all-encompassing, intrusive, regulatory and totalising mode of governance, which seeks to enjoin the entirety of society together in the realisation of ends - and a desire for the state to simply maintain a stable, recognisable and tolerable modus vivendi based on prevailing and longstanding social norms. This is the distinction that really matters, and this is the one which we are now seeing coming to the surface in very stark terms anywhere one cares to look. The tension between the two is becoming more salient, and also more conflictual, and the signs are that it is resolving itself in favour of the shepherd rather than the city. In the next post in the series, I will explain how this calls for a reinvigoration of an intellectual programme which is distinctly and committedly conservative.

Another brilliant and timely piece, David. Two minor comments.

Firstly, it is potentially misleading to view the top-down vision of the state (shepherd-sheep) as having an interest in 'equality', since the bottom-up vision is equally interested in 'equality' - just a different meaning of 'equality'! This is a highly disputed term that is massively overloaded (I realised this issue in my book Chaos Ethics, long before I appreciated its direst consequences). There is some legerdemain involved in 'equality of outcome' approaches; these are frequently concerned with redress and could ultimately never reach a balance point, so 'equality' only has a role by analogy in such approaches. This is parallel to the debate in US jurisprudence regarding 'civil liberties versus civil rights'. I dislike this framing: 'civil rights' in this case are attempts at positive redress, and so this gerrymanders the meaning of (negative) 'rights'.

Secondly, I have been working on this problem (replacing the left-right divide with a meaningful framework) for a few years now, but success requires not only working metaphors but also to provide them in a way that can be taken up more widely. The problem with the Oakeshott framework is that these terms simply aren't going to make it out into common parlance, and although it is strange to be writing that Foucault does a better job in popular clarity here (!), his terms are also unlikely to gain wider traction. Success may also require reframing this issue into at least a three cornered struggle. A tangent for another time, perhaps.

Please keep going! As someone on what used to be 'the left', I view the path you are treading here as much more productive than anything coming from my side of the Old Republic these days.