Is there a Right to Online Pornography?

Thinking through the implications of the liberal theory of porn

If pornography is part of your sexuality, then you have no right to your sexuality.

-Catharine MacKinnon

We have a porn problem. There are, I suppose, still some people who are in denial about this - as though it doesn’t particularly matter in the grand scheme of things that the majority of pubescent boys now routinely watch depictions of sexual violence against women; as though it’s a completely normal feature of married life that the parties should spend an awful lot of time watching other people have sex; as though all of this couldn’t possibly have anything to do with the breakdown in relations between the sexes; as though it couldn’t also possibly have anything to do with the growth in celibacy among the young or the declining birth rate; as though it’s all ‘harmless fun’ or an inevitable feature of growing up. But sensible people all know very well that something odd is afoot in our relationship towards sex, and that sane societies cannot possibly sustain themselves this way in the long-term.

We also know the central dynamic at the heart of the problem, which is the fact that pornography trades on transgression, and as ‘vanilla’ hard core porn has become ubiquitous and normalised, both consumers and producers have been pushed to ever more extreme extremes in search of the necessary level of transgressiveness. On the one hand we therefore see the market expanding ever further into the darkest cellars of the human soul for hitherto-untapped resources of sexual deviance; on the other we see increased competition in the ‘impurity’ stakes on the supply side. It is difficult to know where this ends, other than the sexes becoming set increasingly at odds with one another, and ever larger numbers of people leading unfulfilled, drab, solitary lives as a consequence - and it is hard to imagine that this will allow us to keep interwoven a social fabric that is already serious fraying.

Naturally enough, a pushback is underway. A Conservative peer here in the UK, Baroness Bertin, yesterday (27th Feb) released the findings of her Independent Review into The Challenge of Regulating Online Pornography, originally commissioned by Rishi Sunak when was PM. It is a long report, and deserves detailed exposition elsewhere - and no doubt that there will be much in it that is worthy of both praise or criticism. (I noticed that it, ominously, has things to say about cultivating ‘positive masculinity’.) But its chief recommendation has in any case been widely reported: ‘degrading, violent and misogynistic’ pornography should be banned.

Dealing with the detail of this is going to be tough, however, partly for practical reasons of definition which are well known (what exactly is ‘degrading’?), but mostly because in many ways our thinking about the issue remains mired in various liberal shibboleths that are in urgent need of debunking. And this is one of those odd areas where conservatives and Marxists can find a certain amount of common ground. This is because, to give the devil his due, the Marxian critique of liberal law - that it simply serves to mask or conceal political choice - has a great deal to it. Although, as we shall see, there is a good case to be made that as in so many things Plato might have pre-empted it.

To elucidate all of this, it is worth getting into a time machine and heading back to 1981, and to an influential article that came out in the very first issue of the Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, titled ‘Is There a Right to Pornography?’ It was written by the American legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin (no relation, as far as I am aware, to Andrea Dworkin) in response to the (then) recent report of the ‘Williams Committee’, officially called the Committee on Obscenity and Film Censorship.1

This report had recommended that Britain’s hitherto restrictive laws on obscenity be replaced by a much more liberal regime (in every sense) - essentially restricting children’s access to pornography but otherwise allowing adults to read/watch more or less what they liked within reasonable bounds, albeit in such a way as to make sure that ‘offensive’ material was kept out of public view and that the anything truly degrading, particularly live sex shows or sexual violence, was prohibited. And this is pretty much the regulatory environment familiar to those of us who grew up in Britain before the internet existed, wherein pornography proper was readily available but sold in sex shops or else on the ‘top shelves’ so that children couldn’t access it, and displays of actual penetrative sex were broadly not permitted on TV, in the cinema, in theatres, and so on.

Dworkin, an impeccable East Coast liberal, saw much to admire in the report’s conclusions, and in the article he comes down roughly on the same side of the argument in advocating for a permissive regulatory framework for pornography. But he - as always - thought very carefully about the reasons for reaching the position at which he had arrived. Dworkin entertained the naive, but characteristically liberal, belief that if everybody just thinks very hard we will in the end arrive at the right answer to any moral question. And this comes through very strongly in his thoughts on porn.

Two Arguments for Permissiveness

Dworkin begins with a taxonomy of arguments in favour of general porn permissiveness, which is to say a presumption against censorship. On the one hand there is what he calls the ‘goal-based strategy’, which is what he tells us the Williams Committee adopts. This, basically, involves staking out an argument to the effect that the consequences of censoring or suppressing porn are worse than allowing it to circulate.

On the other hand, Dworkin tells us, there is a ‘rights-based strategy’, and this is the strategy he favours. This, roughly, holds that even if pornography makes society worse off (Dworkin hints that he is of the view that it does), it is wrong to restrict it because in a free society people have a ‘right to moral independence’ which would thereby be violated.

Dworkin’s article is devoted to destroying the goal-based strategy and explaining why the rights-based strategy has to be the correct basis for permissiveness. And his argument is filled with useful insights, both intentional and otherwise. His destruction of the goal-based strategy is convincing, and helps to dispel a lot of the justifications that are trotted out by liberals in defence of adopting a permissive attitude to porn. But his case was being made at a time before the .gif image had even been invented, and when most young people’s exposure to pornography came in the form of images and videos which to the modern eye would appear almost charmingly quaint. I have instinctive sympathy for the broad notion of a ‘right to moral independence’ in the way in which it is framed. But it was always advanced with a sense of blitheness about the perfectly natural, and healthy, desire for parents to bring up their children in a porn-free world.

This blitheness is to a certain extent understandable, because Dworkin was writing at a time at which it was much easier to restrict what children could or could not see, and at which in any event there remained strong social norms acting as a hedge on sexual licentiousness. But the internet has, obviously, radically changed things. And in doing so it has exposed the entire liberal framework within which pornography has hitherto been regulated and understood to be standing on quicksand.

Let’s, first, though, spend a little bit more time going through Dworkin’s central argument.

Goal-Based Strategy

The ‘goal-based strategy’, you will recall, involves an argument that the consequences of suppressing/censoring porn are worse than allowing it to circulate. This, importantly, is different from the JS Mill ‘harm principle’, which Dworkin reminds us is a phantasm and on which the Williams Committee wisely (in his view) placed little weight.

The thing about the ‘harm principle’ is that, as Dworkin puts it: ‘Everything turns on what “harm” is taken to be’. We can probably all agree with the hoary cliché that the freedom to swing one’s fist ends where it causes harm to somebody’s nose. But reasonable people don’t disagree about that - they disagree about public policy, where there is simply no consensus on what ‘harm’ entails or how it should be weighed. As Dworkin rightly points out:

Suppose ‘harm’ is taken to…include damage to the general social and cultural environment. Then the harm condition is in itself no help in considering the problem of pornography, because opponents of pornography argue, with some force, that free traffic in obscenity does damage the general cultural environment.

The fact that people do not often agree on what ‘harm’ is therefore renders the ‘harm principle’ useless as a way of deciding public policy debates. Liberals, take note: ‘conduct should be free unless it can be shown to be harmful’ is never a solution to hard cases, because hard cases always involve a disagreement about what ‘harm’ entails (or which harms are more important than others).

The Williams Committee, though, did not really base its goal-based strategy on the ‘harm principle’, and instead offered a (in Dworkin’s view) ‘special and attractive theory about the general value of free expression’. Here, the argument is that human flourishing requires the existence of a ‘marketplace of ideas’, and that, in the words of the Committee itself:

[W]e do not know in advance what social, moral or intellectual developments will turn out to be possible, necessary or desirable for human beings and for their future, and free expression, intellectual and artistic…is [therefore] essential to human development.

And since this is the case, there simply needs to be a strong presumption against censorship. Nobody knows what is in the end the ‘best’ form of society, and therefore what we need is ‘free expression and the exchange of human communication’ (again, this is the Committee’s phrasing) so that we can consciously negotiate our way towards an outcome that is optimal for human flourishing.

Dworkin attacks this argument on two, linked, grounds. First, and most straightforwardly, as he rightly points out, the ‘marketplace of ideas’ justification for pornography is a justification for completely unrestricted availability of pornography or it is a justification for nothing at all. If ‘we do not know in advance’ what is good in respect of sexual morality and have to figure it out through the free exchange of ideas, then there could be no basis for the Committee recommending that live sex shows be prohibited, as it did. Nor could there be any basis on which it could recommend that public sex remain criminalised - nor, indeed, any basis for recommending (though Dworkin does not raise this issue) that children not be allowed to view pornography. If ‘we do not know in advance’ what is best for human flourishing, then we would not be in a position to judge any of these things.

This is clearly nonsense, as Dworkin intimates, because obviously we do in fact think we know in advance at least some things about ‘what social, moral or intellectual developments will turn out to be possible, necessary or desirable for human beings’ - for instance, we know that it is a really bad idea to let children look at porn or see people having sex in public. And, since this is evidently the case, the ‘marketplace of ideas’ suddenly seems a whole lot less convincing - because if we do know in advance that it’s not good for children to watch porn (and if we do for that matter know in advance that there is something corrupting about live sex shows), then we might know some other things about the ‘social, moral or intellectual developments’ that are ‘desirable’ vis-à-vis other aspects of the issue, too.

Indeed, we might very well decide that, since we know that live sex shows are bad and that children should not watch porn, we also ‘know in advance’ that ‘humans will develop differently, and in fact best…if their law cultivates an ennobling rather than a degrading attitude towards their sexual activity by prohibiting, even in private, practices that are in fact perversions or corruptions of the sexual experience’. And from there any ban of anything is essentially fair game. This is not, I hasten to add, an argument in favour of banning X or Y. It is rather only to point out that the moment anyone who advances a ‘goal-based strategy’ in respect of liberal porn laws concedes there should be some restriction in respect of anything, they must concede that any and all other restrictions could be justifiable on the same grounds. And once this is conceded, the ‘goal-based strategy’ for liberalised pornography laws collapses.

The second, related, line of attack on the ‘goal-based strategy’ is rooted simply in the observation that the political process that is produced by the ‘marketplace of ideas’ will itself, necessarily, ultimately involve restrictions on some things. The whole point of the ‘marketplace of ideas’ is that it is supposed to generate, through free communication, some concept of what is ‘desirable’ in respect of ‘social, moral or intellectual developments’ (since we purportedly do not know these things in advance). But it would be absurd to imagine that, once the ‘marketplace’ has produced this knowledge, people would not act in politics and law to operationalise it. Suppose, then, that within the ‘marketplace of ideas’ a consensus ultimately emerges that pornography should be banned. On what basis could those in favour of the ‘goal-based strategy’ for permissiveness oppose such an outcome?

The ‘goal-based strategy’, which insists that an attitude of general permissiveness to the circulation of pornography can be justified on the basis that the consequences of censorship or suppression would be worse, therefore has little to recommend it. And of course we scarcely need to add that Dworkin’s argument only seems stronger when seen from the standpoint of 2025, when the consequences of the free circulation of pornography are so evidently worse than anybody could possibly have imagined in 1981. On its face, then, the argument that ‘the consequences of suppression or censorship are worse than allowing pornography to freely circulate’ nowadays seems an awful lot weaker than it once did, even setting to one side the other inherent weaknesses in the ‘goal-based’ position.

Rights-Based Strategy

But this, as I earlier made clear, does not mean that Dworkin disagreed with the Committee’s substantive conclusions. Rather, he argued that the only way to get there is by recasting the issue in terms of rights. To Dworkin - and he was admirably clear on this point throughout his long career - the whole point of having a right is that it is a ‘trump’ against utilitarian arguments. If somebody has a right, then this means that it is for some reason wrong to violate it even on the basis that everybody else would be better off, i.e., on the basis of the public interest.

Hence, the right not to be tortured, for instance, only makes sense when understood as a shield against the argument that it would be necessary to engage in torture of somebody for the good of society. If you only have a right not to be tortured so long as it is in the public interest, this is tantamount to saying you have no right not to be tortured at all - because why would a state official be torturing you in the first place if there was no purported public interest benefit (in terms, for instance, of security)?

Dworkin, then, says that anybody who wants to be in favour of a generally permissive approach to pornography has to adopt a rights-based strategy, because it is the only way to actually make a principled case for permissiveness. Bluntly, the rights-based strategy states that people ought to have a right to access porn, and therefore to do so in spite of the fact that it may be harmful, polluting of the cultural environment, degrading, and so on. This, clearly, renders the criticisms of the ‘goal-based strategy’ defunct, because those criticisms are rooted in the fact that it is possible to make out arguments that unrestricted availability of porn would be a bad thing from the perspective of the public interest. The rights-based strategy holds that granting it to be the case that porn is on balance bad for society is still not a reason for prohibition.

The other good thing about the rights-based strategy, as Dworkin saw it, was that it allowed compromise. You will recall that one of the arguments against the ‘goal-based strategy’ was that it was all-or-nothing: there was no principled basis for a halfway house. This is not the case with the rights-based strategy for the simple reason that it is possible to restrict somebody’s access to something without comprising their moral agency. If an adult has to take some additional steps to access pornography in order to prevent it from becoming available to children or offending people who consider it degrading - such as reaching for the top shelf or going into a darkened room behind a curtain - then this does not of itself hinder their autonomy to make their own judgements about matters of morality. It preserves the right while recognising the preferences of the majority in a much more elegant and straightforward fashion than the ‘goals-based strategy’ possibly could, and therefore represents the best approach in a free society - securing autonomy in a way that does not threaten social stability.

The Right of Moral Independence

The thing about the rights-based strategy, as you will have noticed, is therefore that it requires a broader commitment to what Dworkin calls a ‘right of moral independence’. The idea that there should be a right to pornography is contingent on an acceptance that simply because something is undesirable, this in itself is not a reason to ban it - because it is generally more important to respect the moral agency of individuals in making decisions for themselves. Although Dworkin never puts it this bluntly, freedom is in itself a good, irrespective of the outcome - within reason - and in a free society, naturally, the authorities need to err on the side of preserving it.

I have a great deal of sympathy with the basic concept of a right to moral independence in this sense. (Indeed, one of my recent posts was really a defence of it in respect of alcohol.) And I think it is was difficult to dispute Dworkin’s conclusions taken in the perspective of the era in which he was writing. We can grant that he had a typically masculine attitude towards the subject of porn in failing to recognise that the great majority of women who appear in such material have been to some degree exploited or coerced - and that if he had recognised this then his arguments would likely have led him to a very different conclusion. But on its own terms his logic is I think hard to refute.

To lay my cards on the table, then: I think porn is inherently degrading and I do not watch it. I think it objectifies the participants, and I find that in itself objectionable. I think watching a lot of it makes you lose your marbles and corrupts your soul. But I recognise that one could provide reasons why many of the activities I do enjoy, like drinking vast quantities a moderate volume of fine spirits, practicing martial arts, driving a gas-guzzling car, etc., are also in some sense bad. There are plenty of people in the public sphere who would object to those activities on the grounds that they are somehow dangerous, degrading, and/or immoral.

And I think that a defence of individual moral independence, though we don’t usually frame things in that way, is an important safeguard through which adults in a free society negotiate space for individual distinctiveness against the pressure to conform. I also find attempts to censor online speech in the name of suppressing mis/disinformation both laughable and sinister, and I was strongly against the Covid lockdowns - the other significant movements for the suppression of liberty that immediately leap to mind when considering arguments about what people should or should not be free to do.

But I also recognise that we are not now in the era in which Dworkin was writing. Reading his article in 2025, one is struck how old-fashioned, almost naive, its concerns are. I suppose there may be some places in the world where it is still possible to go into a theatre to watch a live sex show. And I suppose some people still buy pornographic magazines. But those activities are now so niche as to be non-existent from a public policy perspective. To all intents and purposes, all pornography is now consumed through a medium that did not exist in 1981, and also in a form - an essentially infinite number of small, self-repeating videos - that could not really even have been imagined.

And it is fascinating to witness the extent to which views about pornography have also changed. Dworkin was able to say, in his very opening paragraphs, that it was uncontroversial that ‘[n]o one…is denied an equal voice in the political process, however broadly conceived, when he is forbidden to circulate photographs of genitals to the public at large, or denied his right to listen to argument when he is forbidden to consider these photographs at his leisure’. But, of course, nowadays many people in fact argue precisely that - that the ability to make and view pornography is a political act which helps them to express and legitimate their sexual identity, and that censoring porn would thereby precisely deny them an ‘equal voice in the political process’.

There are indeed even people around who think that introducing pornography to children is a good thing because it helps them to discover their sexual identity, and who will maintain this even in public argument and in academic journals. And this is not to mention the fact that paedophiles now have ways of exposing children to pornography which were absolutely impossible for Dworkin to even have envisaged - Roblox, for example.

We are, you are sure to agree, therefore simply no longer in the world which Dworkin inhabited at the time of writing. We must recognise that we are now in a world in which the workable modus vivendi which the Dworkinian ‘rights-based strategy’ once allowed (i.e., that adults should be permitted to view most of what they like, provided they are willing to jump through some restrictive hoops that keep it away from children) has to be re-thought, even if its logic makes sense on its own terms.

Indeed, we are now in the position to subject Dworkin’s analysis to critique - and, in so doing, expose the broader problem that lies at the heart of the liberal analysis of not just pornography but any and all issues pertaining to public morality as such. And in order to do this it is worth taking what Marxian critics of liberal law say seriously - namely, that in dressing things up in the language of ‘rights’, liberalism merely conceals decisions about values and thereby takes honest and open political discussion of morality off the table.

The Law Does Not Contain Right Answers

The main criticism always levelled at Dworkin (by some distance the most influential legal thinker of the last quarter of the 20th century) was that he was preoccupied with the idea that, to use his own term, there was always a ‘right answer’ to hard cases. This is a criticism that can be levelled at liberalism across the board: the idea that if everybody just sits around and thinks things through properly on the appropriate basis they will see that, as it were, es muss sein. Hence, for example, as we have seen, if we just apply reason and principle, we can get to the ‘right answer’ about what the regulation of pornography should look like.

The most pointed of these criticisms came from the Brazilian legal theorist Roberto Unger. For Unger, drawing of course on the French post-structuralists and the deconstructionism they spawned, law is characterised by competing oppositions that can be used to problematise its assumptions: law can consist both of rules and ad hoc rulings; it can demonstrate a commitment to freedom or be coercive; it can be public or private; it can take into concern the individual or the public interest; and so on. And the exercise of making and applying law is therefore not a matter of discovering ‘right answers’ but choosing in any one instance between competing priorities or values - it is a matter of giving effect to different normative visions. Typically one of those visions will dominate, and Unger - as one would expect given his Marxian bent - emphasised that it would always be the vision that privileged capital, men, individual autonomy, etc. But the point was that this dominance could be undermined by revealing the fact that underneath the application of law was a fundamentally political choice.

We obviously don’t nowadays live in a world in which law privileges capital, men, individual autonomy, etc., but that is a subject for another post. What I want to emphasise rather is the critical technique being deployed, which is just as apt to be utilised by conservatives as Marxists and which, really, was foreshadowed long ago by Plato. In The Laws, we see the Stranger describing a time long preceding him when men lived in families or clans who had their own customs, ‘habits of conduct’, or preferences. The process of forming the city, which brought such clans together into the first process of political organisation, necessitated the creation of a system of law by a legislator who selected the best customs in order to form the common rules that would apply to everybody. And he obviously selected the best customs (though Plato does not quite spin it this way) politically based on his own intuitions about what was best. Law is, in other words, fundamentally a matter of making choices between competing possibilities - not simply a matter of reasoning one’s way to the right answer in respect of this or that.

I do not wish to open a can of worms on this issue, because I would need then to spend a lot of time discussing whether or not there could ever be ‘right answers’ given effect through law. The point, it suffices to say, about the liberal regulation of pornography which Dworkin espoused is that it presents the application of the right to moral independence as an apolitical choice when it is actually anything but. It is a political choice about the values the law should enshrine. And like all political choices about law it is one which selects one normative vision over another: in this instance it selects the prioritisation of the individual over the collective, and particularly the individual over the family.

It was able to do this because for much of the period of liberal dominance the use of pornography could be concealed and kept within bounds. No doubt it undermined relations between the sexes in general and between husbands and wives in particular in all sorts of ways at the margins. But it did it in a clandestine way that operationalised shame and embarrassment to fairly useful effect. The problem that we now have is that pornography is no longer concealed or kept within bounds but is spilling out into the public sphere in the most unexpected of ways - and this is coupled with a desensitisation to shame, for I suppose self-evident reasons.

And what this means that we are now being confronted - albeit in a poorly expressed way - with the basic division that always lay, let’s put it, latently, within the Dworkinian liberal understanding of pornography: in regulating porn, one is always making a choice about values in such a way as to make a trade-off between who, and what, it is that one wishes to prioritise. What we have elected to prioritise is individual choice and exposure to options. And the trade-off we have chosen is to expose adult relationships and, particularly, childhood, to a tsunami of voyeurism and corruption.

It does not have to be this way because, as Unger and the rest of the legal ‘crits’ were always keen to emphasise, once it has been recognised that law represents a choice between priorities, it then just becomes a matter of entertaining the possibility that it might enshrine a different decision and a competing value-judgement. And this, importantly, is inevitable: we don’t get to escape it by appealing to ‘rights’ as a kind of neutral, objective ‘get out’ through which politics can be avoided. To make this absolutely clear, it is important to address the concern that many readers will have about regulation of porn - concerning freedom of speech - by bringing in Ronald Dworkin’s best and most thoughtful critic, Stanley Fish.

There is Only Politics

Fish and Dworkin had a history: both having been born in Providence, Rhode Island, they became bitter rivals and by all accounts loathed each other - Fish in particular spent a considerable portion of his career crafting articles demolishing Dworkin’s ideas after having decided, early on, that he was going to ‘fuck him in print’. But behind the malice Fish developed an argument concerning freedom of speech which has important implications for the subject at hand.

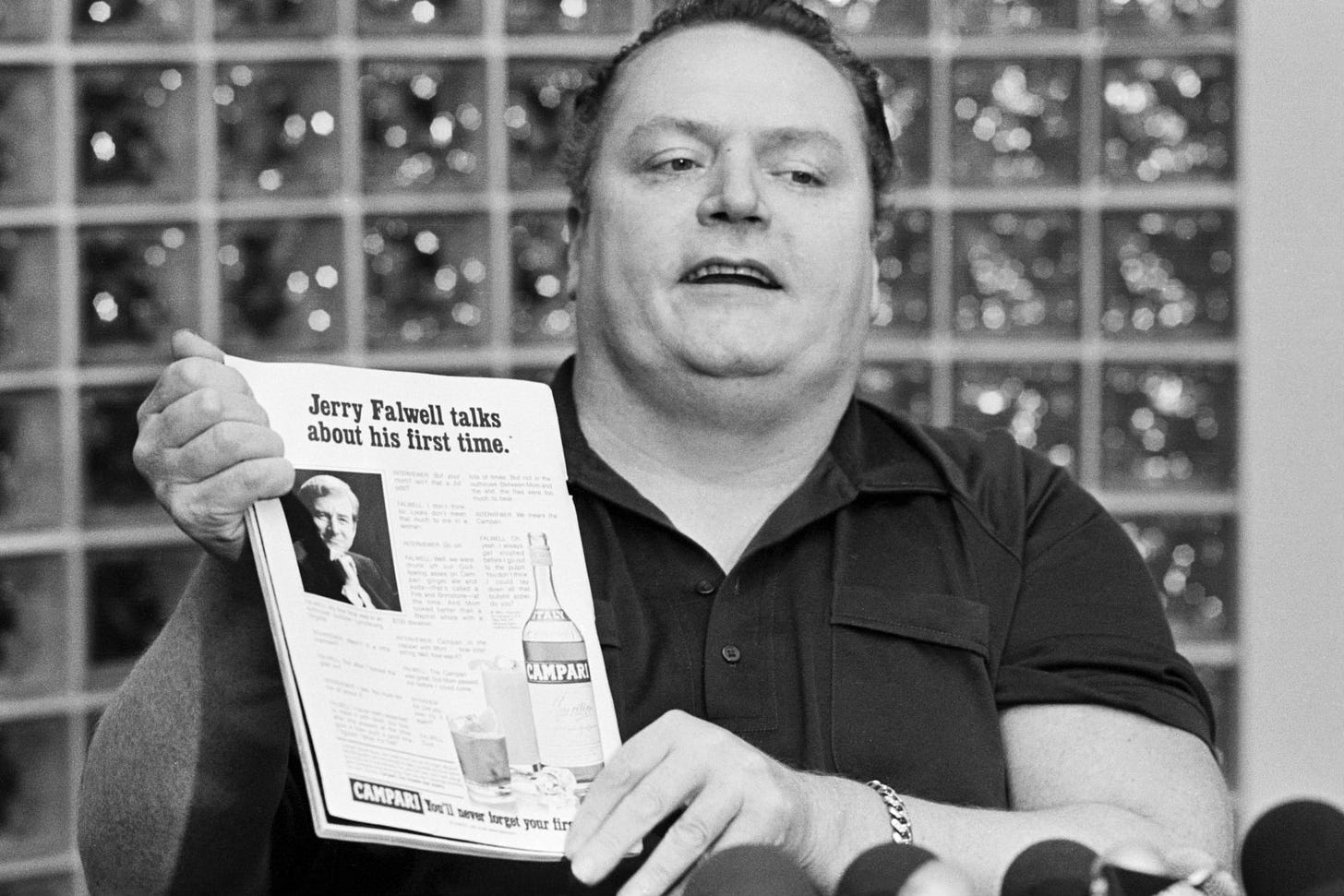

The best case Fish lays out in this regard comes in the article ‘Jerry Falwell’s Mother, or, What’s the Harm?’ Here, he made reference to the decision of the US Supreme Court in Hustler Magazine v Falwell, in which a fake ‘parody’ interview purporting to recount Jerry Falwell’s first sexual experience, with his own mother, printed in Hustler, was held to be permissible on free speech grounds. The Court came to its decision because, in its view, Jerry Falwell was a public figure and had therefore made himself fair game, and in any case the parody interview was part of the ‘free flow of ideas’ and essentially akin to a political cartoon or caricature. Falwell therefore was barred to a claim in libel.

Fish objected to this. As he put it, nobody, even free speech ‘absolutists’, thinks there should be absolute freedom of speech in the sense that anybody should be free to say literally anything: school teachers should not be free to tell young children about their sex lives; advertisers should not be permitted to depict sex acts on billboards; state secrets should not be permitted to be revealed; immediate incitement to violence (what in US jurisprudence is called ‘fighting words’) should be prohibited, and so on. What is really at issue is how much freedom of speech we want, and in respect of what.

What this meant in Fish’s view was that it was not enough to just, as it were, pick up the phone and say ‘free speech’. A rule that simply always applies but for which no justification is ever advanced is in its own way as arbitrary as having no rules at all. No - since in practice nobody is a ‘free speech absolutist’ in the strict sense, everybody implicitly makes value judgments about what speech should be restricted. And this is in effect the same thing as saying that they rely on justifications for free speech, even if those justifications are merely implicit. So what are the possible justifications?

For Fish, there were three plausible candidates for justifications for free speech: 1) it promotes ‘the emergence of truth as the product of public discussion’; 2) it supports individual flourishing; and 3) it is necessary for the ‘serious business of self-government by an informed population’. Fish did not deny any of those justifications - he was perfectly willing to grant them. And he was therefore plain that (and this would be my view, and I suspect most readers of this post) his preferred default was ‘Don’t regulate unless you have to.’ Unless you have a very good reason you should allow speech to be, as it were, free.

But there will, nonetheless, be circumstances in which, ‘reluctantly and cautiously’, it will be necessary to restrict speech which undermines at least one of the three justifications he set out, and which does nothing to promote the others. These circumstances will be, ideally, rare. But the Hustler Falwell-parody should have been one such circumstance. A mean-spirited slur against an innocent woman (it is striking that the Supreme Court seemed to only focus on the effects on Falwell himself, without sparing a thought for the reputation of his poor old mum) does nothing to promote the emergence of truth (it was in fact a deliberate lie), has nothing to do with individual flourishing, and contributes nothing to the ‘serious business of self-government’. And weighed against it was not only its falsity but the fact that it was specifically designed (Larry Flynt said as much) to ‘assassinate’ Falwell’s integrity and thereby undermine his individual flourishing and even his very participation in public life. So why on Earth protect it on free speech grounds?

The point Fish was ultimately making was, then, that ‘rights’ are not an answer to the messiness and imperfections of human life. We do not live in a

cognitive utopia where invariant principles form the basis of unshakable deductions. No accidents, no politics, no bodies, just abstract concepts that speak to one another without interference from base and fleshly appetites.

Ultimately, that is, living in an untidy and difficult world, we are forced always to make value judgements and draw lines - our arguments are really about which values we prefer and where we wish lines to be drawn. We don’t get to simply blurt out ‘freedom of speech!’ and thereby avoid properly thinking about the rules we wish to be governed by. We like freedom and we wish to protect it. But we don’t like untrammelled freedom and we therefore have to try to decide where we want to restrict it.

Fish’s argument is a difficult one - he was well aware that it placed him at the top of one of those good old slippery slopes with which we are all familiar: restrictions on freedom always come with the proviso that they are protecting some other more important value. But his response was straightforward: the choice not to stand on a slippery slope is not available. Human beings are always on slippery slopes because any of the things they hold to be good or useful can be pursued too far. It is therefore no use to complain about the fact - instead one must simply be vigilant that slippage does not take place.

With respect to freedom of speech, or the ‘right to moral independence’ for that matter, and pornography, then, the case Fish would make is clear. It is good to have a general presumption against regulation of pornography for adult consumption. But do we really think that ‘degrading, violent and misogynistic porn’ (which we all know exists in great prevalence) is worth putting up with on the grounds that it 1) promotes ‘the emergence of truth as the product of public discussion’; 2) supports individual flourishing; or 3) is necessary for the ‘serious business of self-government by an informed population’?

And do we really think that there are no competing values that we wish to protect - remembering that the laws we make are the result of political choice? Do we think, for example, that we want our children to grow up in an environment in which degrading, violent, misogynistic pornography is widespread? Do we really want it to be the case that our sons and daughters should be exposed to extreme, hard core sexual images as a fact of life during their formative years? Do we want family life to be preserved insofar as it is possible for us to do so? And do we think that it might be better for the long-term survival of our societies if men and women like and respect one another in the main?

On Moral Dependence

The great Achilles’ Heel of liberal theory is always that it does not have a full (or even partially complete) account for individual interdependence. It understands individuals; it has a hard time with the family, with community, with churches, with society. This has its virtues. As with all things, for reasons already mentioned, emphasising interdependence is a slippery slope with a very undesirable end at the bottom. But it also has its very significant drawbacks, the most central of which being a failure to address or even acknowledge the importance of moral dependence as opposed to moral independence of the Dworkinian stripe.

That is to say, human beings do not get to decide morality for themselves - unless, perhaps, they read a little bit too much Nietzsche in their teenage years. Morality is social. It emerges from the fact that we have to consider the effects of our behaviour on others. Overemphasising the importance of that fact can result in something cloying and oppressive - I mentioned lockdowns, for instance, but one could just as well point to the relentless nannyish hectoring that permeates public life across the piece in contemporary Britain.

But underemphasising it also has its problems, not the least of which is the prevailing ‘as long as everybody is consenting’ attitude with regard to pornography with which we are all familiar. This leads us to a vicious form of purblindness which causes us to overlook the fact that nobody ever consented to the pornification of public life that is so evident all around us. But things have become so bad in that regard that it has now come to the point that serious discussion needs to take place about not rights, but values. How far do we wish the rule of thumb, ‘Don’t regulate unless you have to’, to extend in the digital sphere? And what restrictions would we like to put not just on access but also on content? In doing so we will no doubt be addressing the question of how far we interfere with individual liberty and indeed people’s ‘rights’. But we unavoidably do that anyway, always and in respect of everything, when making law. Our task is therefore to set aside blind adherence to principle and abstract ‘right answers’ and to get stuck into the messiness of politics and values. What, in short, do we want to permit adults to consume, and what do we want to make sure cannot, even by accident, end up being consumed by children?

Dworkin, though an American, was at the time of writing a Professor at Oxford, and was later a Professor at University College London.

One of the things I most enjoy about reading you is the tension I feel at times between my extremely liberal instincts (and historical political stances) and the nascent personal conservatism that has arisen since I saw through the Great Awokening. Your writing is important in this shift, being as I am increasingly convinced by your arguments about the role of the state.

What's interesting sometimes is when I balk. As I have done at this piece. I'm still mentally processing why, but it seems to me that almost all talk of pornography as a 'moral' issue is misplaced. It seems to me that the principle reason that pornography exists is because people are scared to have the sex they want with the appropriate partners. I cannot bring myself to see it as a moral issue at all (unless laws are broken in some way). My intuition is that porn serves as a substitute for full sexual intimacy (in all its mad iterations) because actually achieving it is risky and takes 'balls'. If everyone was having enough fun 'in the bedroom' porn would have much less appeal. I know this from personal experience - I have only ever used porn when my own sex life was either absent or disappointing. Isn't it just another market signal for something?

"Freedom of speech" etc. has become misconstrued. It is one thing for speech as written down, in words, to be free, or the spoken word itself, to be uncensored. Images are a whole different matter, and especially moving images, and images in full colour.

"Erotic" novels, including those by a de Sade or a Georges Bataille, are not in the same category as extreme internet porn, even if what they suggest is scarcely less extreme. The reading experience is indeed wholly different, since imagination is needed to reproduce (depict) in the mind what has been described in words.

A painted image, as displayed uniquely in an art gallery, is not the same a a filmed sequence.

There is another protection which might be used, tho less effective or promising: It is to forbid any money to be made from the display of sexual activity.