'The Government's Assault on Academic Freedom'

On 'manifestations of communion' amongst the new elite

[P]olitical movements rest not so much on rational attitudes as on the fantasies, images, words, and archetypes that come together to make up this or that political kitsch.

-Milan Kundera

There has never been a class of people in all of human history who are freer to express their opinions, no matter how outré they might be, than mainstream, left-leaning academics circa 2023. (The terms ‘mainstream’ and ‘left-leaning’ are in this context almost tautologous.) The evidence is all over Twitter, for anyone who has eyes to see.

But it is of critical importance for members of the ‘new elite’ (as academics undoubtedly are), despite their being part of an elite class, to imagine themselves as being engaged in a David-versus-Goliath struggle against the overwhelming forces of capitalism, conservatism, and so on. And this often means they get very excited by the idea that there are people out there (usually Tory politicians) who are trying to suppress and ‘censor’ their views. This is not remotely rational, given the control this class has over public discourse. But political movements - and the new elite are undoubtedly engaged in a political movement, indeed the political movement of the age - are never rational. They are concerned with symbols, which generate emotional resonances that imbue their members with passion for the cause. And without such emotional resonances they are nothing - mere theory.

This was recognised long ago by the fin-de-siècle French constitutional theorist Maurice Hauriou. What Hauriou noticed was that political movements (like all social groups) are founded on ‘manifestations of communion’ in which the members are all, in one moment, made aware that they share a common feeling. At such times, through repeated affirmations, declarations and acclamations of common ideals, the members jointly ‘obsess’ themselves with those ideals and interiorise them, and this then sustains their shared commitment to the cause across time. These moments, as Hauriou put it (they don’t write academic articles like this any more) therefore:

‘[t]hrow bridges between…states of consciousness like the couplings thrown between railway cars to establish the trembling continuity of an express.’

The members of the movement are in other words physically and temporarily distant from one another aside from these ‘manifestations of communion’, but it is such moments that sustain their emotional momentum and give their project a life of its own across time. Hauriou was writing long before it was possible to imagine the internet, which has put this process on steroids (he was imagining physical meetings of, for example, trade unionists or revolutionaries), but I don’t think his contribution is in any way outmoded by that fact; quite the contrary.

This is aptly demonstrated by a recent brouhaha concerning ‘freedom of speech’ (I use the scare quotes advisedly) for academics expressing support for Hamas and taking various other, slightly-less-outrageous-but-still-pretty-outrageous positions concerning Israel. The facts are substantively rather trivial in the grand scheme of things. But, importantly, they shed light on the way in which our ‘new elite’ functions, and particularly how it functions emotionally - how it is that Hauriou-like ‘manifestations of communion’ sustain that class as it cements its status across time.

This brouhaha largely came to my attention through the website Research Professional, Are you by any chance a subscriber to that site? I daresay you aren’t. Essentially, it’s a website which collates funding opportunities for academics and other researchers. But don’t let that fool you. The site also has a news wing, which, in providing a window into contemporary anxieties in higher education, is a crucially important tool for the informed citizen.1 If you want to know how academics in the UK perceive the world, by and large, Research Professional’s news bulletins are an absolutely indispensable resource. And, sadly, the matter of how academics perceive the world - as you are likely becoming painfully aware - is not just ‘academic’ in the prosaic sense, but a subject of critical importance for how our societies are governed.

Research Professional’s news page was dominated by a single story last week: the Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology, Michelle Donelan MP, and her letter of 28th October to the CEO of Research England (which is the public body in charge of funnelling public cash to universities in England in order to conduct research). In her letter, Donelan expressed concern that some of the members of a recently convened advisory panel on equality, diversity and inclusion for Research England had been tweeting things about Hamas, Gaza and Israel that - how should one put this? - were not entirely suggestive of impartiality. (Indeed some of those things might indeed have sent a message to Jewish researchers that some advisory panels on equality, diversity and inclusion are more equal, diverse and inclusive than others.) In a rare display of gumption, Donelan strongly intimated in the letter not merely that the advisory panel in question should be reconstituted or the members in question removed, but that the entire thing be abolished.

The reaction has been predictable: wailing and gnashing of teeth about threats to freedom of speech (until 5 minutes ago a ‘concocted crisis’), angry tweets about ‘legitimate political discourse’, and public resignations from peer-review colleges and so on.

A lot of this is completely disingenuous, of course, based on either a deliberately or negligently false representation of the issue. The problem here was not really that there was an attempt being made to police offensive speech or expressions of ‘sympathy with terrorism’, which has been the kneejerk interpretation. Donelan was not challenging the right of the academics in question to air their views. She was simply drawing attention to the fact that these people had, on accepting their appointments to the advisory panel in question, signed up to the the Nolan Principles of public office, one of which is impartiality, and also to Research England’s own duties under the Equality Act 2010 which include advancing equality of opportunity and fostering good relations between groups. And openly and outspokenly tweeting support for one side in the current conflict between Israel and Hamas - particularly the latter, given the way in which the boundary between criticism of Israel and outright antisemitism appears to be blurring if not disintegrating altogether - is obviously not consonant with those Principles or duties.

To be absolutely clear: there is no freedom of speech issue raised when one has voluntarily undertaken not to exercise that freedom in certain respects, breaches that undertaking, and then suffers the consequences of having done so. And - as any undergraduate law student will tell you - in order for bias to corrupt a procedure, it does not need to be actually present, but merely reasonably inferred. Would Jewish applicants, or potential applicants, for research funding from a Research England body reasonably infer bias within an advisory panel, some of whose members had recently been prominently tweeting support for Hamas or intemperate statements about Israeli apartheid and genocide? I think they might. And it is appropriate for politicians to be concerned about that, given after all that public money (something academics are always wont to forget comes from taxpayers) is being not just spent, but partly directed, by the body in question.

But this is not the main thing I wish to draw attention to, here. My aim rather is to point out the emotional significance of an episode like this - how it serves to bring mainstream, left-leaning academics together in a ‘manifestation of communion’, and why this makes such episodes so important in keeping the juices flowing.

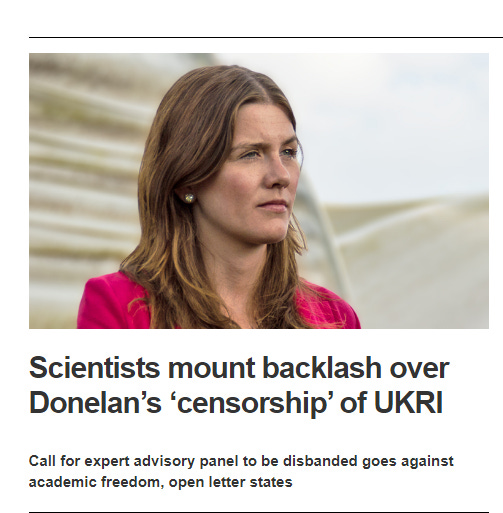

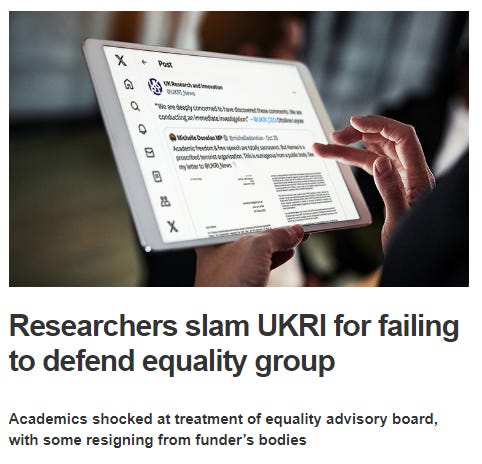

Consider the Research Professional news headlines on the Donelan letter and the way in which they frame things:

Apart from the obvious - that there is essentially no attempt being made to even nod to objectivity or concede that Donelan has her own side of the story - what is particularly interesting about these headlines is the way in which they present a fundamental opposition between academia itself and the politician in question. Note the monolithic and Manichean way in which the dispute is cast. Scientists mount a backlash. Researchers slam UKRI for not showing more of a backbone; academics are shocked. Policy experts position themselves against the goverment. The sense of unity in opposition is palpable.

It is not, in other words, simply that there is a legitimate difference of opinion, here. It is that there are the academics - scientists, researchers, policy experts - on the one hand, and that there is the Tory minister on the other, and one side is good and the other is evil. (The unstated message, of course, is that one side is clever and the other is stupid.) This is not the language of debate, but rather the kind of black and white, ‘four legs good, two legs bad’ thinking that characterises political activism. We, the message is sent, the clever ones, believe in academic freedom and freedom of speech. And they - the Tories - are threatening it.

The communion is digital, then, but it is still a communion, and of a particularly intense kind (and one which spans, of course, not just the pages of Research Professional, but the other online spaces in which academics congregate, such as Twitter and LinkedIn). And in this respect it is like a digital revivalist meeting, within which the members of a shared project come together to reaffirm their values, ‘obsess’ over them, and therefore forge the necessary linkages between ‘states of consciousness’ that will maintain the ‘trembling continuity of [the new elite] express’ as it speeds into the future.

In short, episodes like this are not really to be analysed in terms of their substance, but their symbolic value: as opportunities for like-minded people to re-imbue themselves with the ideals of the movement to which they feel themselves to belong. One of those ideals, in the case of the new elite, is the notion that their activities are fundamentally counter-cultural and challenging to an authoritarian, hidebound and monolithic social order (whatever the evidence to the contrary). And an episode like this - in which a high-handed Tory Minister threatens to ‘censor’ progressive views - therefore has an importance far beyond its real-world significance. It creates the opportunity for a certain set of values to be re-affirmed and further internalised, and thereby for the movement itself to be strengthened.

When thought of in this way, much if not indeed most modern news coverage can be said to take on this function, not exactly deliberately, but generally simply because of the increasing alignment between the opinions of journalists and those of their readers and viewers. We read the news not to be informed, but rather to interiorise and reaffirm our ideals alongside a ‘community’ of people who share them. That this community only really exists virtually, and that we have generally met hardly any of its members (if any at all) in the flesh, does not really seem to matter. Indeed it seems to exacerbate the tendency, since it allows these ‘manifestations of communion’ to happen so frequently and at such scale.

What is particularly alarming about this phenomenon is that it serves to remind us how vulnerable our governing class - senior civil servants, judges, politicians, professionals, academics and so on - are to emotional flights of fancy. The ‘manifestations of communion’ come in a constant flood, and the ‘trembling continuity’ of the express grows ever more violent, and ever more likely to break free from the rails. This, it seems to me, is one of the main reasons why our governance is in such a mess, and why our public life is characterised by such an overabundance of passion. And we should be deeply concerned about the emotional tenor of our age and the effect that the internet has on fostering it.

Naturally, of course, informed citizens aren’t allowed to register to use it. You have to be on the staff at an institutional subscriber.

They're very good at pressing home the advantage, but I wonder if they see it that way. If your ontology revolves around all conceivable manifestations of victimhood perhaps this necessarily involves seeing yourself as the victim too.

It reminds me of when they accuse the right of waging culture war, as if their own worldview is the self-evident truth and that any pushback is necessarily stupid and unjust.

Paradoxically, academia is full of people who are really quite low IQ, and those applying for these research grants are the ones most likely to be susceptible to groupthink and hardly likely to be pushing the boundaries of knowledge with their cultish brains.