Who overcomes

By force, hath overcome but half his foe.-from Paradise Lost

The most important, but least well understood, aspect of modern politics is that there are no final victories. To imagine that politics is a matter of winning and losing is to commit a category error. Politics is the means through which competing values, preferences, interests and desires are brought into something like a stable modus vivendi. And this means that as soon as an election is won, and a different mixture of values, preferences, interests and desires is given a chance to influence decision-making, dissatisfaction grows and competing ideals begin to re-assert themselves.

It is important for those on the political right, currently thought to be on the ascendancy around the world, to reflect on this. You may be familiar with a thought-provoking essay by the writer NS Lyons that recently circulated on Substack, making the case that we are witnessing the return of ‘strong gods’ (borrowing an idea from R. R. Reno). The thesis is easily stated: the ‘closed society’, which was for so long traduced by its liberal opponents as the wellspring of irrationality, hatred, oppression and bigotry (not to mention fascism, populism, and all other ills), is back. We are returning to

strong beliefs and strong truth claims, strong moral codes, strong relational bonds, strong communal identities and connections to place and past – ultimately, all those ‘objects of men’s love and devotion, the sources of the passions and loyalties that unite societies.’

It is a great essay, but I have my doubts about its general thesis. Clearly there has been a ‘vibe shift’ in recent months. But vibes can always shift again. The underlying reason for liberal dominance is old, deep-seated, and so thoroughly woven into the fabric of modern government that it is hard to imagine it will not reassert itself somewhere down the line. And I can’t say that I can see around me in the real world a great deal of evidence of a re-embracing of ‘strong moral codes, strong relational bonds, strong communal identities and connections to place and past’. No doubt we have moved into an era in which all is to play for - a period of ‘regime politics’. But we must remember that in human affairs everything is always ultimately and ineluctably to play for, sooner or later, because nothing is ever fully determined.

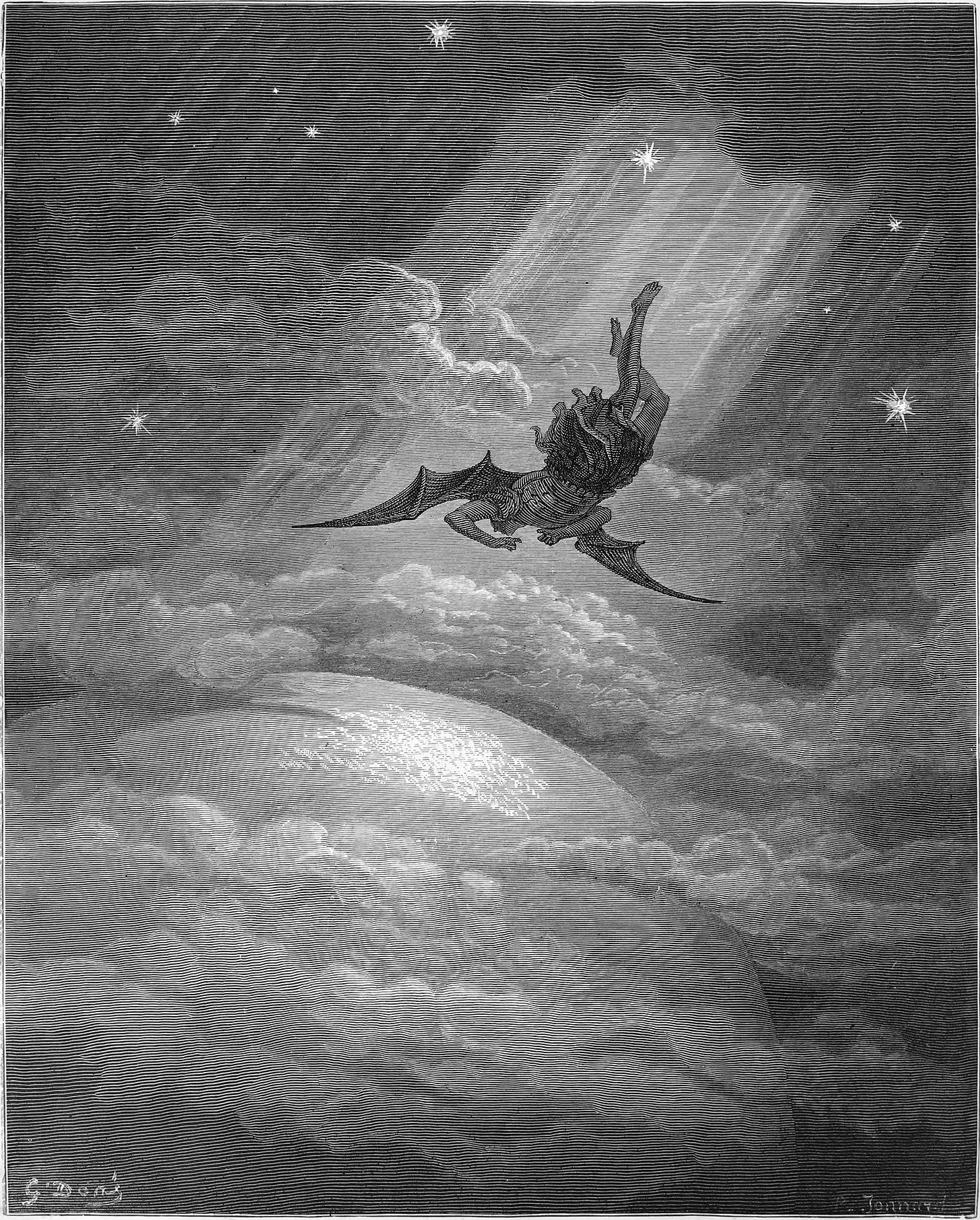

To put it another way, ‘strong gods’ may be returning, but the devil hasn’t disappeared. Last year, I wrote a post in which I (perhaps ever-so-slightly provocatively) advanced a theory of political Satanism, not so as to make any claims about the true existence of the evil one, but to demonstrate that the figure of Satan has powerful semiotic resonances that help us to understand what it means for politics to become entirely secularised. In short, I argued that since Satan can be understood as representative of that force of human reason which conceives of the physical world as all that exists, modern politics - which concerns itself only with the government of the world and spurns all interest in the spiritual and divine - can itself be described as Satanic in its exclusive concern with matters of the temporal. And the result of that exclusive concern, I showed, was the quintessentially Satanic drive to exert mastery over the world itself - an impulse to take total control over each and every facet of human life and thought and the environment in which humans find themselves. As I put it:

If Satan were to have a political philosophy […] this would be its ideal: government of the world, without end; government all the way down; government to the very last detail - perfect government of everything. And everything that government would do in practical terms would in some degree or other gesture towards that totalising end point. And it is no accident […] that secular government should have precisely the same trajectory. This is not because Satan is literally at the helm, but because this is the necessary implication of government unleashed from theological constraint.

And this is a mighty force in human politics. If there is held to be no spiritual or divine aspect to human existence then what purpose does the State have? Its concerns must be purely temporal. And its only purpose in the end therefore can be that of realising desire. On the one hand, those who rule desire power, and to keep it. And on the other, those who are ruled wish their own desires - for security, safety, pleasure, ultimately even happiness - to be met. The result of this is a union of desire between ruler and ruled: Strauss’s ‘political hedonism’ writ large. Mutual desire - for power and for the benefits that power can bestow - becomes that which binds government and society together. And this is a unity which has no end point - the only direction in which government can go is deeper and further in search of yet more desires to meet, lest a rival regime emerge to lay a greater claim on the capacity to grant to the people what they want.

The fact that we live in a secular environment, and therefore a politically Satanic world, a world of political hedonism, has not changed. And I am far from convinced, then, that the so-called ‘strong gods’, if they really are ‘back’, will find their way to dominance. Rather, it seems to me that the forces which modernity unleashed - the semiotically Satanic drive to bend the physical world to mankind’s desire - are as strong as ever. And this means that everything, as always in human affairs, remains to be resolved. All is still to be revealed - as it ineluctably indeed is.

In ‘Croesus and Fate’, Tolstoy gives us a short fable to express this truth. He recounts for us the story (originally from Herodotus) of how Croesus, King of Lydia, and Cyrus, Emperor of Persia, became friends. As the story has it, Croesus - famously wealthy - is trying to impress the philosopher Solon who has come to visit him. Bragging about his great success, he tries to coax from Solon the acknowledgement that he (Croesus) is the happiest man alive.

Solon demurs. For him, the happiest man he has ever met was a poor peasant in Athens who was content with his family and humble home. ‘Call no man happy until he is dead’, the philosopher concludes - the implication of course being that happiness can be snatched away by fate at any moment.

Croesus, enraged, throws Solon out and commits himself to living a life of pleasure. But not long after that his beloved son is killed in a hunting accident. And shortly after that Cyrus, Emperor of Persia, invades, conquers Lydia, captures Croesus, and gives the order for him to be burned alive. Just as the pyre is about to be lit, however, Croesus - realising that Solon was right and that all of his apparent happiness has been snatched away and that he is about to die in sorrow - calls out, ‘Solon, Solon!’ Cyrus, curious what this means, asked Croesus. And on hearing the explanation he decides that he will pardon Croesus and allow him to live thereafter in his court, since he, even as the Emperor of Persia, might too one day find his own happiness overturned by the whim of fate.

Nothing, in other words, is fixed. Nobody should ever imagine that political problems are solvable in perpetuity and that it is open to us to make anything indelibly ‘better’. Human problems are permanent. The best we can do is struggle over the right way to ameliorate them. At times our problems will be dealt with more easily than others. But at any given moment, things can change. Vibes will shift, and shift, and shift again. History will unfold. Events will occur. Strong gods may return. But the devil ain’t going anywhere.

Oh yes. And "my kingdom is not of this world" - perhaps what the end of the long 20th is presaging is a return of theology to the public space. Which will be weird, especially in England, as (for the most part) the official theologians (Bishops etc) are remarkably ill-equipped for the task, being mired as they are in the culture of the weak gods! To speak of the devil in such company is considered deeply impolite...

very interesting! spirituality is a strongly personal trait, perhaps acquired through myths, traditions and a loving family. yet not easily attained in the fast-moving daily realities of the modern, industrialised world with its superficial wealth. the wealthier they are, the less inclined people are to thank the gods, so to speak. becoming further and further removed from nature too makes us less perceptive of our spiritual capabilities. governments should be there only for communal emergencies, politics (indeed) as a means to achieve a balance in the community's aspirations.